By Kyi Cin Thet

Introduction

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, two increasingly contesting stakeholders have emerged, manifesting as the dominating authority and the subordinate public. In this article, authority refers to the government agencies, under which the military and police fall under, and healthcare agencies in the films, both of which have considerably much more power in a disease outbreak. Both stakeholders are perceived differently according to their nationality, due to stereotypes shaped by the nations’ ideologies and cultures. Namely, the American authorities are perceived to be more permissive, while Korean authorities are more draconian (Koo) and hierarchical. The American public is seen to be much more volatile and vocal of their rights (Yan and Babe), while the Korean public are obedient to the authorities, without much vocality (Koo).

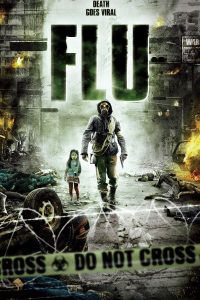

Similarly, the two dominant stakeholders are prominent in the films Contagion and Flu. In Contagion (2011), an American film, the plot revolves around the global spread of a highly contagious virus, and how medical officers, politicians and citizens react to it. Similarly, in Flu (2013), a Korean film, a disease outbreak has broken out in the district of Bundang, and a quarantine is quickly imposed by the district authorities to separate the infected and uninfected. This highly controversial quarantine quickly becomes the cause for the violent riots by anxious citizens held there.

Viewers of the films may assume that the two films present stereotypical differences, further cemented by the differences of setting and language. However, upon closer inspection, the differences in preconceived notions are not as clearly reflected in the two films. Interestingly, the roles of the stakeholders of the two apocalyptic narratives seem to converge, despite coming from different nations, defying current notions of prominent differences between both countries. This article will explore the main and peripheral story narratives and characterisation of different people in the films to uncover how similar notions on the domination of the authorities over public, as stakeholders in the pandemic, are reproduced in both films and how they reconcile the differences between perceptions in reality. This helps the audience identify and appreciate the inherent similarities in roles of the authorities and the public in the films, and by extension, in both countries in the greater context of the pandemic today, by challenging the dominant perceptions and opinions. In this increasingly divided world driven by the pandemic, these two films bring nations closer together metaphysically by shedding light on how the direness of a pandemic causes conflation of certain aspects that were believed to be different, prior to the pandemic. I argue that the comparison of the films merges the different perceived notions of the domination of the Korean and American authorities over their public, bridging the two nations, by recreating familiar and paralleling themes and motifs in pandemic films, tyranny of the authorities, the lack of public agency, and capitalising on shared values of the authorities and the public between nations.

Tyranny of the Authority

The theme of absolute, authoritarian control of authority over the public in every aspect of their lives emerges in both films. Upon the start of the pandemic, the authorities in both films begin to implement measures to stop the spread of the virus, at the cost of individual freedom, by lifting laws that protect their rights, giving the authorities more power to control in pandemics. The effect of the authorities’ measures for the pandemic begins to pervade different aspects of an individual’s life. Both films adopt the concept of quarantine, exposing the public to drastically unfamiliar environments, which greatly changes their surroundings and way of life: In Contagion, the infected are kept within enclosed halls. This concept of tyranny becomes more apparent in Flu, where the uninfected are forcefully, mandatorily quarantined for 48 hours, in small, overcrowded spaces with poor living conditions. While such measures are necessary to contain the disease, the extent of control over their lives is unreasonable. A more malicious intrusion is when everyone is made to strip simultaneously in the same room for a check-up. Similarly, their agency and privacy are stripped off, leaving them vulnerable to the whims of the authorities. They are forced at gunpoint to stay quarantined for more than 48 hours, another display of unbalanced power dynamics, and the authorities’ absolute control over every individual, even with their discontentment and anger. More insidiously, the government decides to incinerate the infected even before they are dead. In Contagion, the authorities’ influence is exerted over people by limiting them to their homes with curfews, and life is greatly displaced from public areas. Dictatorship also manifests as the authorities dictating the distribution of vaccines, which inherently affects how people live. Jory, a teenager, waits anxiously for the announcement of her receiving the vaccine, lamenting that they will ‘lose spring, lose summer’. Their lives seem to entirely depend on the vaccine, which is controlled by the authorities. Both films depict how the lives of the public seem to revolve around the authorities and their greater power to do so, highlighting the tyranny of the authorities.

Both films present tyranny through the theme of lack of authority transparency. Especially in times of a pandemic, when information usually flows top-down due to the authorities operating control to maintain stability, the authorities’ calculated secrecy of important knowledge privy to them is a display of abuse of their power, in the eyes of the public, because it oppresses and limits their actions, influencing their agency. This diminishes their status as free-speaking citizens to crowds of people to be controlled. In Flu, important information about the killing of the infected circulates only amongst the healthcare workers and the authorities above them. With this knowledge, Kim In Hae, a medical officer, protects her infected daughter from the officials, while selfishly exposing the uninfected to the virus as both enter the quarantine. Likewise, in Contagion, officials call their loved ones to instruct them to leave to prevent entrapment within their city which was to be zoned off, whereas many others could not leave in later scenes.

Contesting Public Agency

There is a recurring motif of impending authority control versus displays of public agency in both films. Inherently, both films do showcase acts of public agency, despite the insidious interference of the authorities in their lives. Both films acknowledge that the public possesses power through their ability to riot and protest, which are seen as a means of challenging the authorities and showing disagreement, in order to regain autonomy and agency. However, eventually, the public are made to concede without making any gains. While both films do not assume a top-down approach of handling the virus, the extent of the public’s actions is limited by oppressive authorities. In Flu, the quarantined public riots to leave their quarantine, but they were forced to give up after being threatened with guns, leaving them defeated and clueless about their circumstances. Similarly, in Contagion, protests demanding authority accountability led to nothing. Alan Krumwiede, a conspiracy theorist, undermines the authorities’ reliability and the public’s trust in them by exploiting the scared public to buy forsythia ‘medicine’. He is eventually tracked down by the authorities and is arrested, though it is justified for his spread of misinformation. However, when the most outspoken and subversive character is gone, the sense of power in agency and free speech also diminishes vastly. Ventures displaying public agency ultimately fail, showing the common worry within both films that the public will lose autonomy and power in the pandemic.

While acknowledging the other instances where the individual does eventually reclaim their individual agency from authorities, I reason that still, only the authorities can decide the limits of public agency, essentially meaning that the freedom of the public is still controlled. An individual can continue to fight for their own beliefs on their own accord, whereas the public is still largely regulated. Their lives are not in their hands, but in that of the authorities. In Flu, In Hae, who bravely defies orders and threats to protect her child, does emerge as a victor, but only when the President stops orders to shoot at her, when he realises that her child could potentially hold precious antibodies for the virus. The reclamation of public agency may also be re-interpreted as coexistence of the two stakeholders, after having accepted the futility in fighting the authorities. While characters are much happier and hence freer, there is ultimately no redemption of public agency, just compliance and adaptation to their current oppression. In Contagion, Krumwiede is bailed out and is assumed to be continuing the dissemination of misinformation. However, in his last scene, he is watched carefully by the soldiers near him, insinuating that he will still be kept under the control of those in power, or the authorities. Both films show happy and hopeful endings, but characters are only able to live within the constraints of the authorities. Ultimately, public agency is surrendered to the authorities. The lack of public agency permeates both narratives of the films, bridging differences between the public of two nations.

Mockery of The Other, and Self

Both films mock the other’s aspects and perceptions through negative depictions that are reconciled, upon closer inspection of themes in the films that ironically mirror the themes of those depictions. Both films bring in their opposing counterparts to critique the other means of dealing with the pandemic and its problems, building upon stereotypes and preconceived notions of each other. Unexpectedly, the themes of those depictions are realised in their own characters in different ways. In Flu, an American official orders the mass murder of everyone for the greater good of containment. The willingness to sacrifice morality for pragmatism, mirrors the government’s own earlier measures, when they implemented lockdowns, trapping people inside supermarkets to die, sacrificing the minority to protect the majority. In Contagion, Sun Feng, a Chinese official, kidnaps an American official, to extort vaccines from American authorities for his village. This selfishness, however, emerges in how the authorities, at the sacrifice of others’ safety, protect their loved ones by withholding information. The mockery of the other turns into one of itself when their underlying motives align, even if they culminate in different actions.

Reversal of Perceptions

Beyond defying the preconceived notions, values emerging in the authorities and the public between the two films are reversed. Interestingly, some characters portray a perceived value that belongs to the other nation, introducing unfamiliar notions of the other nations within their characters, which helps us understand the other nations in our context, bridging differences. In Flu, the quarantined mob initiates a riot to leave the quarantine, defying the perception that the Korean public normally obeys authorities and that the domination of the authorities over the public remains even in the pandemic in Korea. Such an instance suggests the adoption of American values by the quarantined public in Flu, where they become more vocal of their feelings. They also emerge as actions that directly obstruct the government’s measures. In a more powerful scene, Oh Ji Goo, a social worker, breaks out the trapped residents in the supermarket, challenging and ruining the government’s plans. In Contagion, there is juxtaposition between the initial anger of the public and the general obedience later, as they quietly queue for the vaccine, suggesting submissiveness to the government, a perceived Korean trait. This causes the two nations to seemingly blend over the convergence of values.

Conclusion

While there are fundamental differences in storylines and characters, there exists parallels in the domination of the authorities over the public between the films, through portrayals of similar values of tyranny of the authorities and lack of public agency. The films also mirror each other through the convergence of preconceived notions, merging them and hence connecting the nations through similar experiences and state of nation in the pandemic, through this re-interpretation of the films. Ultimately, it culminates in the reconciliation of the differences in the stakeholders between the two nations the films are set in respectively, defying current stereotypes and perceptions of the nations, which become minute or peripheral in the pandemic.

References

- Contagion. Dir. Steven Soderbergh. Warner Bros., 2011.

- Flu. Dir. Kim Sung-su. CJ Entertainment, 2013.

- Koo, Jeong-Woo. “Global Perceptions of South Korea’s COVID-19 Policy Responses: Topic Modeling with Tweets.” Journal of Human Rights. 21.3 (2022): 334–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2022.2080497.

- Yan, Wudan and Ann Babe. “What Should the U.S. Learn from South Korea’s Covid-19 Success?” Undark. 5 Oct. 2020. <https://undark.org/2020/10/05/south-korea-covid-19-success/>.