By: Sing Wei En Wayne

Introduction

Detroit: Become Human’s (2018) intricate and purposeful design of its locations, characters and even how they interact with one another leaves much room for gamers to interpret different social themes presented in the video game. What seems most intentional and visually apparent of the critically acclaimed action-adventure video game is that its allusions to the treatment of androids by humans are metaphors for racial prejudice and bias against the American Black community.

The game takes us through the lens of the three playable android characters, Connor who is designed to work in law enforcement, Kara who is a housekeeper and Markus, a caregiver. The three main characters, similar to all androids in the country, are regarded as objects and do not have the same rights as compared to humans. Through the eyes of the androids, players of the game can see how androids are typecast and treated like second class citizens in society.

Interestingly, what appears intransitive is the fact that the marginalised group, the androids, possesses no physical differences from their discriminators, the humans, as seen in Fig.1. Also, one of the leading bases of racial discrimination is due to a difference in physical appearance, such as skin colour, as compared to traits that cannot be observed simply by looking at the individual, as posited by Harrison and Thomas (2009, p. 159). This would arguably make androids not an ideal metaphor for commentary on the themes of Black discrimination intended in the game.

Despite this, I believe that depicting androids to look similar to humans was intentionally done to present a larger underlying commentary. Detroit Become Human references a “universal theme of a divided society”, and is not a commentary on “specific social issues”, as shared in an interview by one of the creators, Adam Williams (Lemne, 2018). Upon playing the game, one might surmise the specific social issue he was referring to was Black discrimination. Responding to the creator’s admission that the main intention is not just to allude to racial discrimination, I argue that the androids are not only a metaphor for the racial discrimination of the Black community, but also a metaphor for the emotional experience of discrimination as a whole. The gameplay puts players in the perspective of a marginalised group, allowing them to vicariously experience the treatment that different forms of marginalised groups are subjected to. Though it reveals the universal experience of marginalised communities, it also shows that there is potential for change.

In this opinion article, I will start with a quick overview of the game’s racial allusions to the Black community. Then, I will delineate the universal experience of social labelling, followed by discrimination. Thereafter, I will explain how exceptions to the rule show that social stigma is an uneven experience. Finally, I will expound more on how the medium of video games allows players to empathise with the characters they play as.

The Typical Reading: Depicting Androids as Metaphors for the Black Community

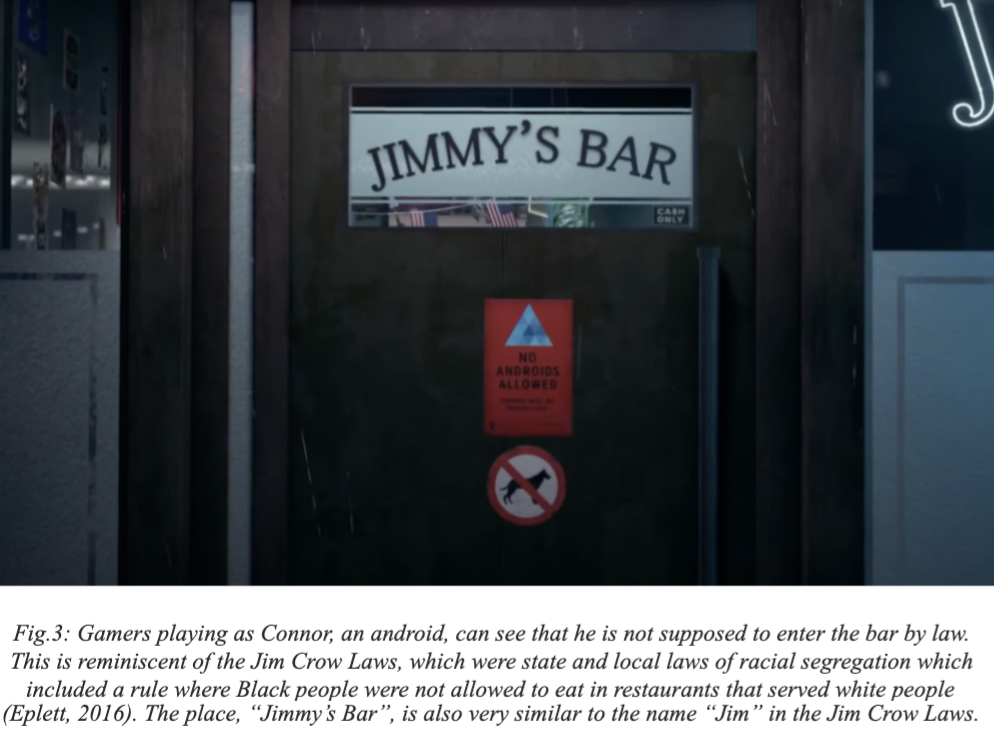

Detroit: Become Human purposefully uses several visual elements and motifs to remind gamers about themes of racial discrimination and how the androids are metaphors for the Black community, who were also similarly discriminated by society in the past. Choosing Detroit as centre stage for this game is especially significant due to its unique racial composition and its long history of racial riots. The largest racial group in real-world Detroit is the Black community at 78% of the city’s population (“Detroit Demographics – Get Current Census Data for Detroit, MI”). Fueled by discontentment of injustice and racial discrimination, the riots led to 43 dead, over 1000 injured and more than 400 buildings destroyed (Emeka, n.d.). The game makes several references to America’s 1896 “separate but equal” doctrine. The government could make social rights such as housing, medical care, employment, education, transport and other services be segregated by race, as long as equal access was given to each race, as seen in Fig.2 and 3 (“Separate but Equal”).

Despite these allusions, the differences between androids and humans in the game have nothing to do with their physical appearances, but rather their social labelling as android. This suggests to me that the main theme is the universal experience of discrimination through the imagined metaphor of androids. These imagined scenarios allow players to connect this experience to a broader scope of marginalisation, rather than it being a specific type of discrimination.

The Experience of Being Essentialised: Imposing the Social Labels of “Androids”

Detroit: Become Human traces the origins of social labelling and demonstrates how it leads to social stigma. Social labelling can be names that are officially given by society, such as the term “android”, or informal monikers used in everyday life such as “plastic” or “machine”. This is reminiscent of derogatory stereotypes used to demean individuals, such as the Jewish having a large “Jewish nose” (Ullmann, 2020). These informal labels can often be of a negative connotation and used by individuals to distinguish and separate marginalised groups from them. Interestingly, the experience of discrimination due to stereotypes is universal to all androids and is not based on their skin colour. Thus, the experiences of discrimination by androids are not referring to any specific racial groups, but any marginalised group instead.

Labelling is formed not only by the perception and recognition of differences, but also by the social significance of that difference. However, it is not necessarily so that a differing appearance from the norm would result in labelling that creates social stigma. In society, an individual’s unique eye colour that differs from the norm may not create social labelling as it does not have social significance to people (Green et al., 2000, p. 201). Gamers playing as Kara doing household chores will come across a news programme showing that unemployment levels in Detroit had reached 37.3% in America, as seen in Fig.4. A large number of androids joined the workforce and supplanted many jobs previously held by humans, leading to widespread resentment and disapproval of androids by the human working class, as seen in Fig.5. Humans who have had their jobs replaced by androids will have a preconceived negative sentiment of the term “androids” and associate androids with a negative label, giving it social significance. These generalisations used to negatively stereotype certain groups could lead to an implication known as social stigma (Link & Phelan, 2001, p. 363).

The Consequence of Social Stigma: Discrimination in Detroit: Become Human

The concept of stigmatisation is contingent on the discriminator having access to some form of power over the marginalised group that allows them to first identify differences, create generalisations and sort them into labels that discriminate. This is supported by Link and Phelan, who aver that stigma exists when people associate differences with negative stereotypes, in order to create a separation between them and the labelled, making the labelled disadvantaged due to discrimination and a loss of status (2001, p. 367).

This can be seen when comparing how Fowler, Connor’s boss at the police station, speaks with Connor as compared to Hank. Fowler first speaks to Hank, a human, with eye contact. After ending the conversation with Hank, Fowler goes back to doing his work and ignores Connor. If the player, as Connor, chooses the option to introduce himself before leaving the office, Fowler will avoid his eye contact and interrupt the player mid-sentence by asking him to leave, as seen in Fig.6. In a different dialogue option, he calls Connor a machine before asking him to leave.

What is interesting about Detroit: Become Human is that the reason androids are discriminated against is not because of their difference in physical appearance from the humans but by their social labels. A study references Goffman’s treatise which separates an individual’s stigmatised characteristic into one that is visibly apparent, which they posit as “the discredited” and one that is more invisible, which they refer to as “the discreditable” (Chaudoir et al., 2013, p. 75). They assert that social stigma is often based on the overall public perception of the group, as opposed to initial impressions “the discreditable” make on others (Chaudoir et al., 2013, p. 78). In Fig.7, a civilian begs Connor to save her daughter, looking at him in tears. However, upon glancing down at his android uniform, she realises that Connor is an android and demands that a human policeman take on the task instead, as seen in Fig.8. Androids, in this case, are “the discreditable” as their differences are not easily visually discerned at first glance. This demonstrates the pre-existing social stigma that humans in the game have towards androids.

The Uneven Experience of Social Stigma in Detroit: Become Human

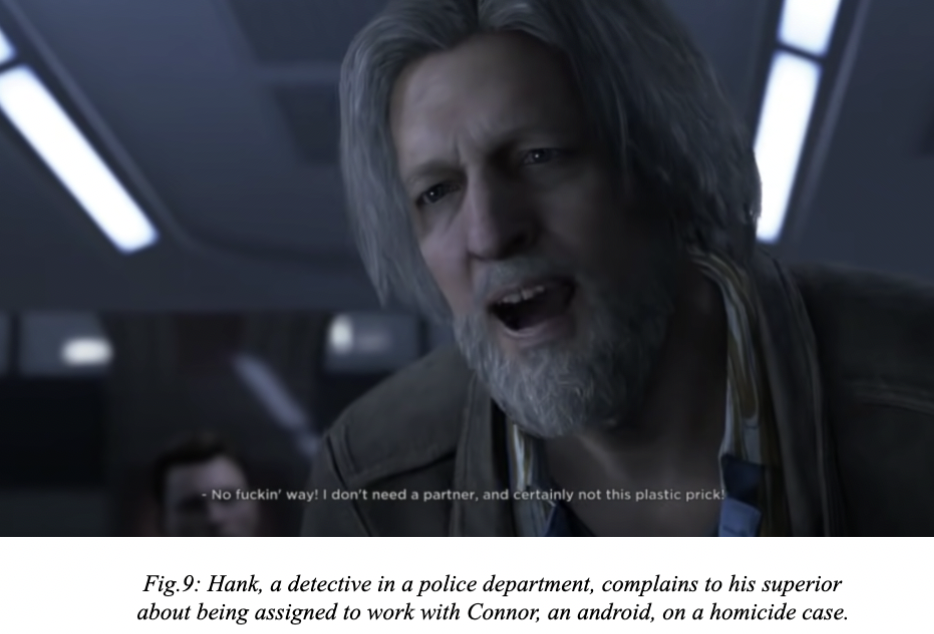

Despite the negative social labelling of androids, there is a disparity in how well androids are treated by their owners. The game effectively compares how androids Connor and Markus are initially treated differently by their owners, with Connor being treated badly and Markus being treated well. This social stigma is not the result of individuals being different, but rather the byproduct of previous interactions between people with that difference and others who think of that difference negatively (Chaudoir et al., 2013, p. 76). This is seen in Fig.9 when Connor is initially treated rudely by Hank, his co-worker, due to his previous negative preconceived impression of androids. Hank is rude to Connor and calls him a “plastic prick”.

The game interprets the act of discrimination as a construct that can be conditioned by one’s past experiences with that specific group. Hank blames the death of his son on androids after an android surgeon failed to save his son’s life during an emergency surgery caused by a car accident.

Conversely, not having any previous negative experiences with androids could result in humans not having a social stigma on androids. Acclaimed human painter Carl, has a good relationship with his caregiver android Markus. Carl does not have a negative preconceived notion of androids and the two develop a father-son relationship. Carl does not confine Markus to doing tasks that a normal caregiver android would be restricted to and encourages him to try painting, as seen in Fig.10 and 11.

Though an individual’s past conditions the way they might view a certain group, it is also possible that they can realise that their past preconceived notions are misguided and let go of their prior prejudices. Depending on the player’s choices of dialogue with Hank, they might form a close friendship and change his perception of androids. A possible outcome is seen in Fig. 12, where Hank disregards his own life when helping Connor to save the androids.

The Universal Feeling of Stigma: Video Games as a Storytelling Medium

Detroit: Become Human’s immersive gameplay effectively conveys emotions felt by the marginalised through themes of social stigma. Green and Brock posit this concept as narrative transportation, where users are completely immersed and invested in the story they are shown (2000, p. 701). Players vicariously make decisions from the perspective of these marginalised androids, identifying themselves with the characters in the story. Players manifest the character’s goals and emotions, fostering a sense of empathy (Tal-Or & Cohen, 2010, p. 404). A study argues that different narratives in the media can induce “empathic processes” which can improve perceptions of stigmatised groups (Oliver et al. 218). Readers became more solicitous and created more positive evaluations towards these marginalised groups (Oliver et al., 2012, p. 219).

By experiencing social stigma for themselves from the perspectives of androids, the game intends for players to subconsciously or consciously develop empathy for the marginalised. When the marginalised androids are subjected to discrimination by humans, players are forced to make difficult decisions. This is seen in Fig.12 and 13, which show the possible choices that gamers playing as Kara have to make after she runs away from her abusive owner.

Featuring over 40 different final endings, players are put in moral dilemmas and given the power to make consequential decisions that affect how the game unfolds. With possible endings resulting in the character’s death, players are encouraged to be careful of the choices they make. As players are immersed in different imagined scenarios, they can understand the emotions felt by the discriminated against throughout the game.

Conclusion

If we abstract the arguments from previous sections, it can be seen that though there is a universal experience of discrimination in terms of labelling and stigma, this is not a uniform experience for all androids, as seen in Fig.14. Depending on the android’s owner, this experience may also vary.

By placing players in positions where they experience discrimination for themselves, it seems that the game wishes for players to rethink the way they label and treat groups different from them. It reminds players that though discrimination is bound to stay, whether they are part of it is ultimately their choice. Indeed, when we say Detroit: Become Human, the hopeful outcome is that players become more human themselves and realise that we have more in common than what divides us.

References

Chaudoir, S. R., Earnshaw, V. A., & Andel, S. (2013). “Discredited” versus “discreditable”: Understanding how shared and unique stigma mechanisms affect psychological and physical health disparities. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746612

David C., & Adam, W. (2018) Detroit: Become Human (Playstation 4 version) [Video game]. Quantic Dream.

Emeka, T. Q. (n.d.). Detroit riot of 1967. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Detroit-Riot-of-1967.

Eplett, L. (2016, March 29). Eating Jim Crow. Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/food-matters/eating-jim-crow/.

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Green, S., Davis, C., Karshmer, E., Marsh, P., & Straight, B. (2005). Living stigma: The impact of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in the lives of individuals with disabilities and their families. Sociological Inquiry, 75(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682x.2005.00119.x

Harrison, M. S., & Thomas, K. M. (2009). The hidden prejudice in selection: A research investigation on skin color bias. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(1), 134–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00433.x

History. (2010, February 3). Montgomery Bus Boycott. History.com. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/montgomery-bus-boycott.

Lemne, B. (2018, May 2). Detroit: Become human isn’t about racism or sexism. Gamereactor UK. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://www.gamereactor.eu/detroit-become-human-isnt-about-racism-or-sexism/.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Separate but equal. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/separate_but_equal.

Oliver, M. B., Dillard, J. P., Bae, K., & Tamul, D. J. (2012). The effect of narrative news format on empathy for stigmatized groups. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699012439020

Tal-Or, N., & Cohen, J. (2010). Understanding audience involvement: Conceptualizing and manipulating identification and Transportation. Poetics, 38(4), 402–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.004

Ullmann, J. (2020, November 9). Understanding the antisemitic history of the “hooked nose” stereotype. Media Diversity Institute. Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://www.media-diversity.org/understanding-the-antisemitic-history-of-the-hooked-nose-stereotype/U.S. Census Bureau Quick facts: Detroit City, Michigan. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/detroitcitymichigan/PST045219.