by Mah Xiao Yu

The dark, desolate desert landscape in Mad Max: Fury Road produces a sense of ominous foreboding and despair.

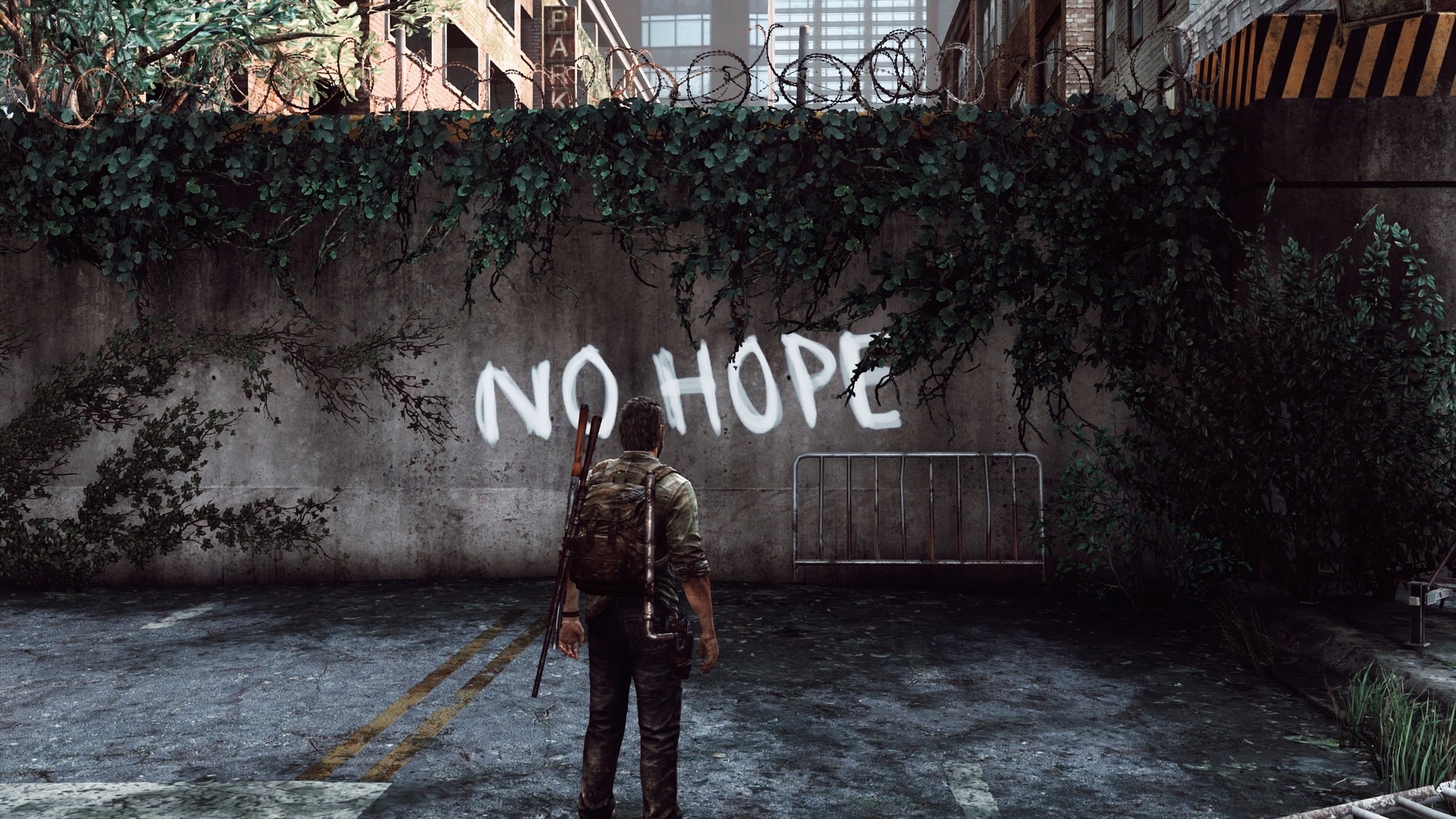

Meanwhile, in The Last of Us, nature reclaims the city landscape, sending an optimistic message of nature’s post-apocalyptic restoration.

We can arrange post-apocalyptic landscapes on a spectrum of beauty: grim images of desolation on one end, and vibrant restored natural landscapes on the other. At large, “ugly” landscapes seem to imply pessimism and despair, while beautiful landscapes are associated with awe and hope. For instance, the vast and barren desert in Mad Max: Fury Road immediately inspires despair through its dark colours and the audience’s own associations of the desert with a lack of life and a struggle to survive. Hence, the oppressive wasteland enhances the film’s violent plot and overall pessimistic portrayal of the post-apocalypse as hostile to human life. On the other hand, the city landscape overrun with colourful flora and fauna in The Last of Us (TLOU) fuses the familiarity of the city and the utopian dream of an Edenic world. Read at surface level and in the current context of environmental deterioration, such a landscape gives us a beautiful, optimistic vision of a more hospitable post-apocalyptic world.

However, the assumption that beautiful post-apocalyptic landscapes, which typically feature large-scale natural restoration, offer a simple message of hope and optimism misses their posthumanist undertones. Hope in the post-apocalypse typically means the main character surviving yet another day, survivors rebuilding society, or in general, the world as we know it eventually being restored. These are humanist ideas of hope that put humanity at the forefront. However, beautiful natural landscapes in post-apocalyptic media express a unique type of hope: hope for natural restoration. This shift in focus from humanity to nature and the environment is characteristically posthumanist. While the idea that such beautiful natural restoration coincides with humanity’s tragic demise is recognised by most viewers, the full extent of the landscapes’ posthumanist message is largely overlooked. In discussing the empty streets and abandoned houses now overrun with nature in TLOU, the game’s developers wanted players to “reflect about how much we’ve built […] and what we’ve lost” (Druckmann and Wells 1:16-1:22). The gameplay reflects this decision: stories uncovered through the landscape, such as letters and diaries, are mostly about people. Hence, it can be said that the posthumanist hope for natural restoration is superseded by the humanist despair at humanity’s demise.

Therefore, using TLOU, which is representative of the trope, I argue that beautiful post-apocalyptic landscapes are more than just aesthetic backgrounds for the plot to unfold, and instead deliver a thoroughly posthumanist message of humanity’s insignificance and the irrationality of its survival, an idea that runs directly counter to the plot of most post-apocalyptic texts—humanity’s struggle to survive against all odds. This is because the resilience of landscapes as well as their peaceful beauty juxtaposed with human agency and human nature reveals how transient, terrible, and tiny humanity is.

The landscape as a storyteller

To understand how beautiful landscapes convey posthumanist narratives, it is important to examine how landscapes in general have narrative power. Viewers understand landscapes intuitively based on their emotive effect. So, when presented with a landscape that makes them feel awe or comfort, viewers interpret the landscape in optimistic ways. Hakon Heimer’s theory of “restorative” natural environments can then explain for us why the natural landscapes in TLOU inspire feelings of hope and, as a result, optimism (117). Heimer identifies four environmental features that are closely associated with positive feelings: “ecodiversity,” “synesthetic tendency (a commingling of colors, smells, and other sensory stimuli),” “environmental familiarity,” and “cognitive challenge (which includes structural complexity and texture)” (117). In TLOU, flora and fauna have overtaken cityscapes, and, in an iconic scene, giraffes peacefully roam free, demonstrating restored ecodiversity. Synesthetic tendency and cognitive challenge come through the vibrant colours and textures in the game’s graphics, which have only become more realistic as game development technology improves. Finally, the landscape still retains environmental familiarity even with drastic ecological restoration since TLOU takes place in recognisable cityscapes. Hence, the natural environment brings viewers relief and peace in between moments of stressful violence in the game and also gives viewers the hope that once Joel and Ellie, the main characters of TLOU, fend off all dangers and find a cure for the “zombie” infection, they will one day be able to live such a peaceful life.

TLOU, as a video game, further empowers its landscapes to not only provide brief respite to pace the plot, but also deliver their own narrative. Regardless of writers’ intentions, video game landscapes have gained narrative independence from the plot since viewers are not passive but rather active players who move around and explore the diegetic world with much more freedom than in other media. Matthew Potteiger and Jamie Purinton argue in Landscape Narratives that spatial (as compared to textual) narratives empower the viewer to examine and experience the landscape with their own direction and pace, and hence interpret the narrative in their own way (10). While TLOU limits the landscape open for exploration according to players’ progression, players are encouraged to explore beyond what is strictly necessary for the plot, as doing so helps them uncover clues for how to proceed and acquire upgrades for the player’s equipment. But beyond bonuses that help with gameplay, the landscape also reveals narratives not directly related to the plot. For instance, the graffiti on walls not only reinforce the atmosphere of societal collapse, but when actually read also reveal nuances in the post-apocalyptic world such as the desperation of the survivors or civilians’ cynicism towards the government.

It is interesting that while the game’s plot unfolds through human actions and dialogue, the story of the larger world is left to the landscape to tell—through graffiti, unread letters, and abandoned diaries—which points to the absence of other storytellers, namely human storytellers. I argue that the landscape’s resilience and beauty, which gives it its position as the storyteller, hence demonstrates a posthumanist shift in power that is examined in Leif Sorenson’s The Apocalypse is a Nonhuman Story where the “indifference [of non-human objects] to events that are cataclysmic for humans suggests that representing the apocalyptic requires a break from human scale and an acknowledgement of nonhuman modes of agency” (526). In stark contrast to the landscape, humanity is transient, terrible, and tiny.

The posthumanist landscape

Even with stories about humanity and society, humanity has lost its agency as its own storyteller to the landscape and is hence unable to fully possess even its own narrative. While most post-apocalyptic humans cannot speak for themselves simply because they are dead, this nonetheless demonstrates how human agency is undercut by humanity’s frailty and transience. In contrast, the landscape is resilient—the graffiti people paint onto walls will remain to tell their tale, long after they are dead. However, the landscape is far from passive in this transfer of power. In TLOU, nature proves humanity’s transience by actively encroaching on and taking away humanity’s power and agency. Unlike in many other zombie apocalypse texts, the “zombie virus” in TLOU is not an escaped man-made virus that demonstrates humanity’s destructive greed but is rather a fungal infection (inspired by Cordyceps) that originated from crops. The infection that possesses and mutates millions of human bodies in gruesome ways can hence be read as nature forcibly taking back its space and agency from humanity.

However, far from being an unreasonably cruel and vengeful force, nature and its beautiful restoration prove that humanity should not be given power or agency due to its inherently terrible and exploitative nature. Most players recognise that the deterioration of humanity does not simply coincide with the restoration of the natural landscape, but it is only because of humanity’s catastrophic demise that such restoration is possible. Yet, players still hope that the characters will persevere and find a way to rebuild society, even if this naturally means rebuilding towns and eventually wrestling the environment back from nature, tarnishing the very beauty players are appreciating now. To take the posthumanist message to its full logical conclusion, humanity has not only been a disruptive force but what we consider the cornerstones of humanity—civilisation and technology—are antithetical to the landscape. The humanist hope that the world as we know it can be restored and the hope that the beauty of the natural world can be maintained are mutually exclusive.

Players who are optimistic about human nature may reject this out of the hope that a post-apocalyptic society will cherish the environment more. However, post-apocalyptic texts like TLOU, which are more concerned about the immediate survival of its human characters, do not offer any evidence for why that would be the case. Rather, TLOU presents a largely pessimistic picture of human nature. In contrast to the beautiful landscape, humans are visually associated with gory violence and atrocities they commit. But in an almost paradisiacal landscape, where there is enough shelter, food, and water for the small population of survivors, the responsibility for most, if not all, the terrible violence and pain characters must suffer is set squarely on humanity. Humans are solely responsible for the “every man for himself” chaos that gives rise to groups like the cruel Hunters, who lure other survivors into their territory before killing them and stealing all their supplies. Hence, even when TLOU affords these characters agency, it is only of the worst kind.

Ultimately, post-apocalyptic landscapes inherently overwhelm all else with their non-human scale, such that it seems humans never will or never had any real power or agency to begin with. While characters’ stories start and end, and the plot’s events begin and conclude, the landscape remains unchanged and outlasts the entire story and all other actors. Rarely do we have a post-apocalyptic text that ends with a large-scale revival of humanity, who goes on to reclaim the landscape from nature. Rather, the personal, local stories of the characters conclude without any impact on their larger surroundings, regardless of how dramatically life-altering their experiences and actions may be. This makes beautiful post-apocalyptic landscapes not so different from their “ugly” counterparts. Although less overtly grim, they are still overwhelmingly vast in comparison to humans, who are tiny in their isolation and dispersal.

Hence, beautiful landscapes present us with an irony within post-apocalyptic texts. The main point of these texts revolves around humanity’s struggle to survive by whatever means necessary, and yet the landscapes point to how insignificant humanity is and how the struggle is not only ultimately without any lasting impact but also destructive to humanity itself.

Conclusion

The posthumanism of beautiful post-apocalyptic landscapes tells us that there can be hope for nature to recover and even prosper after apocalyptic events, but there is no point in humanity’s struggle to survive, as all it would only tarnish the beauty of the world and bring about its own suffering. As Kafka once said, “there is hope, an infinite amount of hope, just not for us.” Yet, despite the irrationality and futility of it, as humans, we cannot deny our desire to live. There is no hope for us—but just as being transient, terrible, and tiny is in our nature, it is also in our nature to hope, and it might be the only form of agency we have that cannot be taken away from us.

Works cited

#505. Image. Evan Richards. The Cinematography of Mad Max: Fury Road (2015). https://www.evanerichards.com/2016/4687.

Heimer, Hakon. “Topophilia and quality of life: Defining the ultimate restorative environment.” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 113, no. 2, 2005, pp. 117.

Jackson. Image. Jackson. https://thelastofus.fandom.com/wiki/Jackson.

Joel and Ellie watch giraffes. Image. Pete Nikolov. My Thoughts on The Last of Us 2. 1 Jul. 2020. https://medium.com/@pete.nikolov/my-thoughts-on-the-last-of-us-2-9dd3233d675f.

Mad Max: Fury Road. Directed by George Miller. 2015.

PlayStation. “The Last of Us Development Series Episode 2: Wasteland Beautiful.” 2013, April 9, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZJ2C6wAVpg&feature=youtu.be.

Potteiger, Matthew, and Jamie Purinton. Landscape narratives: Design practices for telling stories. John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

@softorzabal. “the last of us + graffiti.” Twitter, 15 Jun. 2020, 6:38 a.m. https://twitter.com/softorzabal/status/1272297472057057280?s=20.

Sorenson, Leif. “The Apocalypse is a Nonhuman Story.” ASAP/Journal, vol. 3, no. 3, 2018, pp. 523-546.

The Last of Us Part II. Image. Jade King. 12 Jun. 2020. https://www.trustedreviews.com/reviews/the-last-of-us-2.

ViceyVERSUS. “The Last of Us – Giraffe Scene.” 2013, June 18, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMjdl_uYXgE&feature=youtu.be.