Redefining What “Super” is in Superhero, Akira as a Transformative Enabler in Zom100: Bucket List of the Dead (2023)

By: Zhong Baode

Introduction:

Traditionally, as superheroes are a subset of heroes, qualities superheroes usually encompass qualities of heroes, and the difference has been understood through the presence of extraordinary abilities such as overwhelming strength, exceptional intelligence, or access to technology surpassing human capabilities. Beyond these powers, superheroes are also defined by their mission and identity, which typically aligns with a clear moral good and a prosocial purpose and a symbolic representation that embodies this mission (Coogan, 2013, p. 4). Superheroes are often positioned in relation to their corresponding supervillains, whose actions create the narrative conditions that allow superheroes to enact and affirm their mission.

However, Zom100: Bucket List of the Dead (Kawagoe, 2023) blurs this distinction by reframing what counts as “super” through a protagonist who appears entirely ordinary. Akira Tendo, an overworked salaryman in Japan, is abruptly thrust into a sudden zombie apocalypse without any traditional superpowers such as enhanced strength or advanced technology. Instead, the series foregrounds a different kind of power: super emotional intelligence. Akira’s defining ability lies in his capacity to sustain hope and agency for himself and those around him despite the collapse of society. His handwritten bucket list, initially created as a personal reminder to live fully before death, becomes a source of motivation for his companions and gradually evolves into both his mission and emblem. Even as a zombie comedy, the series mirrors the structural features of a superhero narrative. It presents a clear origin moment that liberates Akira from his oppressive life, introduces a sequence of escalating encounters with threats that test his ideals, and positions psychological trauma and despair as recurring villains that return in cycles. Within this narrative framework, Akira also presents his own set of mission and identity, along with his extraordinary emotional adaptability, it effectively positions him as a superhero in a zombie apocalyptic context, even in the absence of physical or technological advantages.

This essay argues that the definition of “super” should expand beyond traditional physical or superintelligence to include cognitive and emotional capabilities that are extraordinary in specific contexts. By studying Akira, I will first demonstrate how his actions position him as, first a hero, then a superhero within the zombie-comedy framework. I will introduce the concept of the “transformative enabler,” arguing that in the unique environment of a zombie apocalypse, Akira’s extreme emotional intelligence (EQ) empowers this concept into a genuine, life-saving superpower.

Zom100 Background:

Zom100: Bucket List of the Dead is a Netflix Japanese animation that begins in a world reflecting modern Japanese society’s emotional exhaustion. Its protagonist, Akira Tendo, is an overworked salaryman crushed by corporate exploitation, his daily life reduced to submission and routine. His despair is specifically driven by his abusive boss, Kosugi, who enforces a culture of overwork and psychological torment. When the zombie apocalypse suddenly destroys Japan, Akira’s first reaction is not fear but ecstatic liberation as he realizes he will never have to go back to the office, but uses this as a chance for a new life (Kawagoe, 2023).

Akira being happy not needing to go work anymore

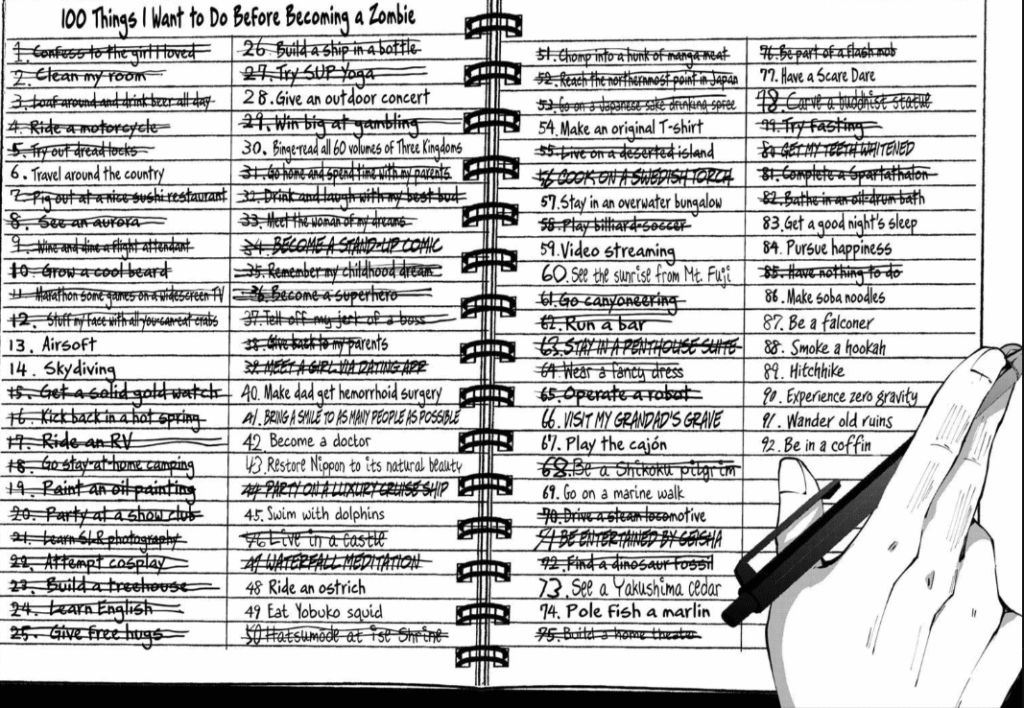

From this newfound freedom, Akira creates a handwritten bucket list of things he wants to do before he becomes a zombie. The slowly growing list that displays his long-lasting wishes, includes goals that are both humorous and sincere such as “confess to the girl I love, drink and laugh with my bestfriend, become a superhero and give back to my parents” (Kawagoe, 2023). But it also serves as a moral and emotional compass that transforms the apocalypse from a struggle for existence into a journey of rediscovering the meaning of life. Through this simple act, Akira asserts that to live fully, one must first reclaim the right to dream.

Akira's bucketlist notebook (Image from u/GeneralMedia8689, 2023, r/Zombie100, linked here)

At first glance, the story introduces its characters as they struggle to survive the apocalypse, but as it progresses, brief flashbacks reveal their lives before the outbreak and portray them as individuals trapped in the rigid patterns of Japanese society. This background becomes a primary source of villainy because it shows the psychological constraints they carry into the new world. Akira’s actions then gradually liberate them from these burdens. For instance, he liberates his friend Kencho, who was emotionally trapped, ashamed of his failures and unsure how to live without the societal structure that once dictated his worth. He also supports Shizuka Mikazuki, who was mentally trapping herself in a cage of control. She developed a hyper-rationality and emotional suppression attitude after growing up under the strict guidance of a father who emphasized success, efficiency, and pragmatism (Kawagoe, 2023).

However, Akira’s journey of liberation was severely tested when he later encountered his old boss, Kosugi, who had successfully established a corporate hierarchy among survivors. This reunion reintroduces Akira’s deep-seated trauma, causing him to regress instantly into a submissive, self-doubting salaryman. It is at this crucial juncture that Shizuka, recognizing the source of Akira’s paralysis, uses his bucket list notebook to shatter the psychological hold Kosugi has over him, reminding Akira of the self he had fought to become.

Akira relapsing into his former submissive self

The show demonstrates that the primary villains in Zom100 are not merely the zombie horde, but a spectrum of psychological oppression: deep-seated trauma, the emotional traps that mask Kencho’s happiness, Shizuka’s emotional suppression, and Akira’s self-doubt, all of which must be conquered to sustain true freedom.

Definition of Heroes and how Akira is one:

Heroes can be understood as individuals who embody certain personality traits and often act for the collective good even at great personal cost. Allison and Goethals identify the “Great eight traits of heroes” as “smart, strong, selfless, caring, charismatic, resilient, reliable, and inspiring” (2011, p. 61), which together form the foundation of how societies perceive heroes. Heroes can also be defined by an act during a critical moment, elevating their status even though their prior lives have not been marked by heroic deeds. Throughout the series, Akira’s actions clearly establish him as a conventional hero within the narrative frame of the zombie apocalypse. He consistently demonstrates care and selflessness in protecting both his friends and the people he encounters. His heroic courage and willingness to sacrifice himself are especially evident during his confrontation with the giant zombie shark in Episode 8, where, in a desperate attempt to save Kencho and Shizuka, he deliberately places himself in harm’s way and uses his own body as bait to lure the creature away from them (Kawagoe, 2023).

Transformative Enabling as a Superpower:

To qualify Akira as a superhero, we need to first establish his superpower as it’s a common prerequisite for identifying a superhero. To do so, a contextual definition of power needs to be established. In the setting of Zom100, as discussed earlier, the true crisis is the psychological paralysis and trauma inflicted by the loss of hope and deep seeded psychological trauma and less the immediate physical threat of the zombie apocalypse. In this environment, Akira functions as a “transformative enabler”, where he elevates the collective strength of a team by empowering them with hope and motivation. His power manifests primarily in two ways that seem “super” in this context.

First, his hightened EQ allows for super perception and liberation. Akira is able to instantly read and react to the deep-seated emotional needs of his companions, granting him the ability to dismantle their psychological barriers. For Kencho, Akira intuitively understands that the zombie threat is less paralyzing than the fear of social judgment,he enables Kencho to openly pursue his dreams even when facing death. For Shizuka, Akira constantly challenges her self-imposed prison of hyper-efficiency, knowing that without emotional connection she would never be genuinely “living” as a human. This ability to initiate and manage profound psychological shifts in others leads to the second ability of his super resilience and motivational energy. His emotional capacity to pivot from despair to hope in the face of societal destruction is extraordinary. This emotional resilience that got channeled into his bucket list notebook, functions as both his symbolic emblem of identity and a physical, unshakeable source of purpose that external circumstances cannot destroy. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, one of the greatest factor in surviving trauma is the presence of an internal locus of control (believes that the events in their lives are largely a result of their actions) and high adaptation ability (2014, p.32). Akira’s commitment to his list clearly demonstrate why his mentality is so reslient and his ability to communicate his mission to his peers inspire them to do so as well, manifesting as motivational energy for his entire group. This notebook is a crucial identifier that helps both his peers and himself anchor their actions to a positive mission of surivival.

Akira as a Superhero:

However, superpowers alone are not enough to elevate a hero to superhero status, since the superhero genre is defined by four fundamental pillars: power, identity, mission, and narrative structure (Hammonds, 2021, p. 2; Darowski, 2014, p. 3). The key attribute of the superhero’s mission is its non negotiable and enduring nature. Gertler, as cited in Darowski (2014), notes that superhero storylines tend to fall into four broad categories: the origin story, the escalating conflict with a villain, the aftermath of a major confrontation, and the never ending cycle of subsequent attacks that continually retest the hero’s mission (p. 12). The threats in such narratives typically escalate beyond what normal institutions can contain, requiring extraordinary intervention to save a community or the world.

Over time, however, the superhero genre has gradually redefined what counts as a villain, and this in turn reshapes the kinds of missions superheroes undertake and the scale of intervention required. As Darowski (2014) observes, modern superheroes are often depicted as deeply flawed and internally conflicted, with their primary struggle shifting from external enemies to inner demons such as self doubt, guilt, or the consequences of their own power (p. 8). A film like Logan (Mangold, 2017) follows a recognisable superhero plotline, yet the central “villain” is arguably Logan’s own self loathing and trauma. If villainy can be internal or systemic rather than purely monstrous or criminal, then the superhero mission can also shift from saving the world to healing a community, or even helping individuals confront their own psychological burdens. At the same time, the notion of superhero identity has also evolved. Coogan’s classic definition emphasised the duality of a superhero’s public and private persona, alongside a distinctive codename and costume (2013, p. 4), but many recent heroes such as Iron Man, Captain America, and Doctor Strange no longer maintain secret identities. Their superhero identity is instead anchored in symbolic markers like costumes and emblems that condense their mission into a visual form. Identity can therefore be understood less as a rigid double life and more as the recognisable image and narrative role that signal the hero’s commitment to their mission.

The scale of a mission and symbolic marker is also profoundly contextual. Batman’s determination to protect Gotham using the Bat Signal works because both citizens and criminals recognise that symbol, yet it would lose much of its power outside that context. This suggests that the stakes of a superhero mission are not defined only by global visibility, but by the depth of transformation experienced by those within the hero’s immediate sphere of influence.

With the relevance of scale and types of villainy in mind, superhero texts such as WandaVision (Shakman, 2021) show how superhero conventions can appear within hybrid genres, blending domestic sitcom, psychological drama, and superhero narrative. In WandaVision, the familiar structures of origin, escalating conflict, and recurring threats unfold without a single cosmic villain, since the central antagonistic force is Wanda’s unresolved grief and the harm it inflicts on the residents of Westview. The stakes are largely confined to this one town, and the mission becomes one of release and emotional reckoning rather than planetary salvation. These developments prepare us to recognise forms of superheroism that operate on a smaller, more intimate scale, where the main battle is against exhaustion, despair, or trauma rather than purely physical annihilation.

Within this framework, Zom100: Bucket List of the Dead can be read as a superhero narrative that relocates familiar generic features into a zombie comedy. As previously argued, Akira already possesses a superpower in the form of extraordinary emotional and adaptive intelligence, so the remaining pillars to consider are mission, identity, and narrative structure.

The series satisfies the “extraordinary mission” criterion by substituting the global save the world mantle with a smaller scale duty to save lives and restore the will to live. Akira’s immediate sphere of influence consists of his travelling companions and the scattered survivors he encounters. In a context where institutional responses have collapsed, his unconventional superpower is precisely what is needed to sustain hope and purpose. His handwritten bucket list functions as a mission statement that commits him to living fully and helping others reclaim their desires, this transform those around him for the better, showcasing the depth of transformation experienced by the immediate circle of influence

The bucket list also becomes central to Akira’s superhero identity. Just as Captain America’s shield condenses his mission into a single recognisable object, Akira’s notebook operates as a portable symbol of his commitment to life and freedom. Although he does not maintain a permanent codename or costume, the bite proof suit he dons during the giant zombie shark incident in Episode 8 not only fulfils his childhood fantasy of becoming a superhero, but also lets him enact his mission by saving civilians. For those he rescues, the sight of this costumed figure willingly throwing himself between them and the threat marks him as something more than an ordinary hero. This act of superheroism continues to shape how others see him even after he sheds the suit, as he remains the protector whose notebook functions as a moral compass. This is most evident when Shizuka uses the bucket list to help Akira recover his sense of self and resist Kosugi’s attempts to drag him back into a corporate hierarchy.

Akira in his bite-proof suit protecting a civilian

The narrative structure of Zom100 also closely mirrors a conventional superhero arc. It opens with a “normal world” in which Akira is trapped in a soul crushing corporate routine, stages an origin incident in the sudden zombie outbreak that paradoxically frees him, follows a rising action of road trip episodes and moral tests that call him to act for others, builds toward climactic confrontations with the main antagonist, and finally gestures toward an open ended cycle of ongoing threats, both psychological and physical. Crucially, the villainy in the structure, operates on multiple levels. Alongside the continuous physical danger of the zombie horde, the series repeatedly reintroduces psychological villains such as corporate exploitation, internalised self doubt, and social conformity, all of which threaten the characters’ physical and emotional survival. The late season antagonist Kanta Higurashi crystallises this multi layered villainy. Like Akira, he uses a bucket list as a tool for organising survivors, but his list is filled with malicious and self indulgent desires that treat other people as expendable. Kanta functions as Akira’s dark mirror, a classic superhero trope in which hero and villain share similar abilities and narrative positions yet embody opposing moral orientations. Their clash recasts Akira’s emotional and adaptive intelligence as a superpower that must be defended against its own corrupted double, reinforcing the idea that what truly distinguishes a superhero is not simply the presence of power, but the way that power is directed.

Taken together, the contextual scale of Akira’s mission, the evolving understanding of superhero identity, and the series’ adherence to core superhero plotlines support the claim that Akira Tendo is not only a hero but a superhero whose defining power lies in his capacity to transform the inner lives of others.

Conclusion:

By analyzing Zom100: Bucket List of the Dead through the established criteria of the superhero genre, it becomes clear that the narrative functions as a sophisticated, modern deconstruction of the traditional hero archetype. The series successfully subverts the focus on external, physical dominance by centering its conflict on the internal, psychological threats of corporate trauma, conformity, and despair. Akira Tendo, devoid of physical superpowers, is elevated to superhero status by his transformative emotional intelligence (EQ), that helps him provide psychological support in dire situation which is just as important to the physical survival. This ability, manifested through the symbolic emblem of his bucket list notebook, allows him to act as an enabler, restoring purpose and liberating the collective will of his immediate community. By staying through with his mission (living his best life), he ultimately combats the shows’ villains (deep-seated trauma), and its plot structure (the never-ending cycle of attacks) onto the superheroism framework. Zom100 proves that the measure of the “super” should include also extraordinary EQ in specific context and ultimately, confirms that the most powerful hero in a world defined by mental exhaustion may be the one who can inspire others to simply remember how to live.

References

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What they do and why we need them. Oxford University Press.

Coogan, P. (2013). The hero defines the genre, the genre defines the hero. In R.S. Rosenberg & P. Coogan (Eds.), What is a superhero? (pp. 3–10). Oxford University Press.

Darowski, J. J. (2014.). The superhero narrative and the graphic novel. In G. Hoppenstand (Ed.), Critical insights: The graphic novel (pp. 3–16). Salem Press. https://www.salempress.com/Media/SalemPress/samples/cigraphicnovel_samplepgs%5B1%5D.pdf

Hammonds, K. (2021, August 31). The globalization of superheroes: Diffusion, genre, and cultural adaptations. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1112

Kawagoe, K. (Director). (2023). Zom 100: Bucket list of the dead [TV series]. Bug Films.

Mangold, J. (Director). (2017). Logan [Film]. Marvel Entertainment; Kinberg Genre.

Shakman, M. (Director). (2021). Wandavision [TV series]. Marvel Studios.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services: A treatment improvement protocol (Treatment Improvement Protocol Series 57). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207192/