Samurai Jack (2001-2017) and the Pedagogy of Hope

By: Lim Lyn-Zhou

Introduction

When Samurai Jack first aired in 2001, audiences met animation’s unorthodox superhero: a stoic samurai attempting to save his family and country, flung from feudal Japan into a far-future world ruled by the shapeshifting demon Aku. Jack’s mission was clear—defeat Aku and “return to the past”. Despite the fantasy setting, Samurai Jack was every bit a superhero: heroic mission, exceptional abilities, a magic god-forged sword (Aku’s only weakness) and a moral code that forbade him from cruelty. Despite its apocalyptic premise however, the first four seasons rarely felt apocalyptic. Episodes were bright adventures with talking dogs, disco robots and comic villains.

Unserious characters and animated atmosphere

Success or defeat, each half-hour ended with Jack still hopeful, ready for the next quest: an unserious and constant tit-for-tat exchange between the samurai and evil. The world had ended, but Samurai Jack’s tone insisted that goodness would prevail.

Jack is haunted by nightmares and an Omen taunts him to take his own life (right)

Twelve years after the fourth season aired, the series was revived on adult-programming platform Adult Swim, and everything had changed. Set 50 years after the previous episodes, Jack has lost his sword, wanders through a decayed wasteland haunted by visions of his dead parents, and in one harrowing, kid-unfriendly scene, nearly commits ritual suicide, seppuku. Even Aku, once a manic trickster, is bored by his own eternal reign.

Aku seeks therapy in a comedic sequence

The shift from Cartoon Network’s episodic format to Adult Swim’s serialised format erased the reset button: no stand-alone adventures, no easy restoration of virtue, and no assurance that goodness will suffice. Such drastic tonal breaks are rare, which usually keeps characters relatively consistent for returning viewers. Here, the familiar hero image collapses, and the apocalypse finally feels real and depressing. The question is: what role does this despair play in Samurai Jack, and why focus on it?

Holding that thought, Samurai Jack’s revival also mirrors its audience. The children who once watched after homework time returned as adults facing economic precarity, political volatility and environmental dread. Season 5 meets this generation where they are, seemingly translating their exhaustion into narrative. Its darkness resonates not because the fictional world worsened, but because its audience has matured into an era where endurance is key to adulthood in their own ‘apocalypse’.

Season 5 therefore, makes despair the stage-setting theme of its story. As Jack’s setbacks accumulate, his sword—the symbol of his purpose—and the portals that once offered a way home, have vanished. C. R. Snyder et al. describe hope as a “positive motivational state” based on two abilities: the capacity to see possible routes to a goal (pathways), and the energy to move along them (agency) (2002, p. 250). Thus, when both vanish in Jack’s world, despair takes over.

Michael Milona observes that despair is more than the absence of hope, involving pain or suffering. (Milona, 2020, p. 100) Jack’s torment and pain result in psychological paralysis, where suicide constantly weighs heavily on his mind. Yet Milona redefines hope that “we can have hope without optimism… a person can hold on to hope even as they begin to expect that their hope won’t be fulfilled” (pp. 100–101) In Season 5, despair plays this role: stripping the world of any optimism so that only hope—now understood as the will to act amid failure—is the obvious default.

These allow the essay to argue that Samurai Jack has become an especially effective study in resilience and hope for an audience now grown into tumultuous adulthood. It removes the ‘reset’ structure after each episode, rendering despair and the process of the self overcoming it visible, and establishes the importance of community in recovery. Season 5 ultimately shifts hope from mere ‘feel-good’ optimism to a set of deliberate actions. This sets the stage for how other animated or superhero media can reimagine the way it appeals to the realities of newer generations.

This ‘pedagogy of hope’ is taught by the show’s design—an emotional ‘architecture’ that models how to face despair and grow through it.

The Emotional ‘Architecture’ of Samurai Jack

Jack is tormented by the Omen (left) and the ghost of his father (right)

Season 5’s figures—Aku, the Omen and Ashi—function less as plot devices than as mirrors of Jack’s internal states of turmoil and triumph. This guides the audience through the cycle where hope declines, endures and is renewed. Aku, the shapeshifting demon, represents entropy, time’s paralysis that halts Jack’s progress, a key driver for his depression. The Omen externalises Jack’s guilt, confronting him with the fear that his purpose is lost.

Jack’s despair reaches its peak when he kneels for seppuku, but is stopped by Ashi, a young assassin raised from birth to hate and kill him. Ashi, by contrast, embodies renewal. She begins as his enemy but awakens to empathy, mirroring and fueling Jack’s rediscovery of purpose. The series uses these relationships to chart a process of the depletion and regeneration of hope.

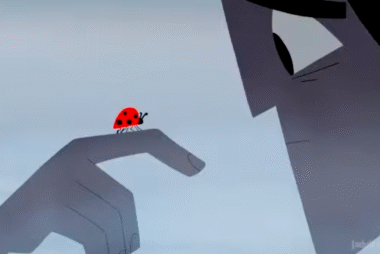

Ashi hesitates killing Jack when his care for life (left) reminds her of a ladybug in her childhood (right)

This process forms the show’s ‘pedagogy of hope’ — a structure that teaches how growth emerges from despair. Imagine a tree mirroring Jack’s road to recovery, hope first takes root when he chooses life over self-destruction by refusing suicide, echoing Viktor Frankl’s claim that meaning begins in the will to live even amid suffering. It strengthens into a trunk with inner discipline that resists the winds of despair, aligning with Albert Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy—the belief that perseverance in action restores agency. Lastly, with Barbara Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory that positive social bonds expand the capacity to endure, its branches and leaves grow outwards when Jack regains strength by connecting with others. The following analysis has these three stages—roots, trunk and branches—corresponding to Jack’s refusal of suicide, his rebuilding of discipline and his rediscovery of community.

Permanence of Loss: Making Hope an Act of Choice

By removing the episodic resets that once erased every failure, Season 5 shows that having hope is no longer automatic, but a deliberate choice made in the face of lasting loss and despair. Earlier seasons always ended in renewal: time paused, wounds vanished overnight, optimism came freely. Following the 2017 revival, Jack’s rugged appearance and missing sword mark time’s progression where every wound leaves a trace. Without comfortable resets, both Jack and the viewer must now live with the consequences of each defeat instead of waiting for restarts.

As Frankl notes, “man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.” (Frankl, 1992, p. 32); Jack still possesses the freedom to act despite losing external control. Frankl then emphasises these actions as “the last of the human freedoms to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances” (p. 32), which are freedoms that do not themselves create meaning but make meaning in the face of suffering possible. Jack’s refusal to the Omen’s command to end his life, despite unchanged external circumstances, reclaims that freedom and opens a path to create meaning. Frankl then emphasises that “meaning is available in spite of—nay, even through—suffering…provided the suffering is unavoidable.” (p. 64) Unable to change what causes him despair, Jack’s endurance of his pain turns despair into purpose. This decision marks the first root of hope—to live even when nothing can be restored. Through the permanence of loss and the conscious decision of persistence, the series teaches both hero and viewer that this endurance is the foundation on which all later forms of hope are built. After all, if Jack succumbs to suicide, there is nothing left to discuss.

Jack fights the urge to end his own life, and regains his sword.

Learning Hope Through Confrontation and Discipline

If hope sprouts from the choice to live, Samurai Jack shows that it endures only when the self learns to live with despair—through discipline that brings one’s emotion into balance. Season 5 often deliberately slows its pacing to fix the audience’s focus on Jack’s struggle with despair. In scenes where he sits in silence amongst flora or argues with his demons, cinematic choices like long pauses, haunting echoing sound design and the lack of background music stretch each moment of failure into reflection.

The meditations (left) and the mental battle with himself in the spiritual realm (right)

These sequences make coping a visible act more than an intangible feeling; endurance appears as a process that must be practised. Episode 7 focuses this process into ritual. Jack, on the road to spiritual recovery, meditates and enters a spiritual realm, meeting a monk. His task: to brew a cup of tea to unlock the path to his magic sword. Jack’s tea is not up to par, which the monk judged to “lack balance”, drawing Jack’s ire. The problem the audience realises is Jack’s imbalance, not the monk. On the second attempt, each careful motion of the ladle and each controlled breath marked small acts of self-regulation, contrasted with his shame and irritation with the monk. Albert Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy clarifies this progression. Bandura explains that confidence in one’s capacity to act grows through “master experiences”—moments when one confronts failure, corrects errors and succeeds through persistence (Bandura, 1997, p. 80). Jack’s “mastery” lies not in combat but in recognising that his anger blocks his renewal. When he dispels his hallucinated self and restores composure, his balance and his sword return.

Jack regains his old outfit and sword.

Bandura adds that people strengthen this sense of control through “vicarious experience” when they observe successful models who recover from setbacks (p. 81). Jack’s repeated patterns of frustration, reflection and calm offers a tangible structure of coping. Viewers see that hope is the work of rebuilding the self. Frankl complements Bandura’s claims. Meaning is remade within endurance as Jack’s acceptance of suffering as unavoidable gives purpose to his discipline. In the essay’s metaphor, this discipline forms the trunk of hope: solid not because storms are avoided but because it holds firm through self-restraint and discipline.

Shared Endurance: Community as the Final Branch to Recovery

Jack’s hope now survives, but to thrive, hope must grow outwards. Jack’s recovery unfolds with Ashi, who protects and believes in Jack while he seeks balance. When Jack kneels to kill himself in Episode 6, the scene divides into two opposing forces: the Omen (guilt) and Ashi (the voice of compassion). The Omen’s accusations —“Death lies in your wake” — embody despair, inward guilt and self-destruction. Ashi’s response reverses the pull to self-destruction: “Hope you gave me saved my life! [The Children] You saved them!” Her words restore a world Jack can no longer see. Frankl describes this as the point meaning becomes possible amongst suffering — “being human always points…to something other than oneself.” (Frankl, 1992, p. 50)

Ashi learns of Jack’s noble stories from his old compatriots (left). She pleads with Jack to not end his own life (right)

Ashi’s encounters with communities that owe their survival to Jack’s compassion reshape her beliefs, allowing her to confront Jack with concrete proof that his life mattered. In the final battle, Ashi and Jack’s old allies’ defence of him shows recovery expanding from two to many. Barbara Fredrickson’s “broaden-and-build” theory clarifies these positive connections that expand one’s ways of thinking and acting, “build[ing] enduring personal resources” (Fredrickson, 1998, p. 307). Fan service aside, these nostalgic cameos are especially testimonies to Jack’s efforts, widening his perceptions beyond failure, helping him build inner ‘resources’ to push forward. Lev-Wiesel adds that growth after trauma depends on “confidence in and commitment to one’s social environments” (2008, p.148). Ashi creates that environment, the branches of hope that grow with more support systems. Season 5 teaches the viewer that ‘to go far is to go together’. Hope is not just a solitary self-improvement game but something we build with others to last in the face of despair.

Conclusion

Season 5’s design aligns perfectly with the reality of the generational zeitgeist. Fans who saw Jack as a symbol of optimism returned in 2017 as adults familiar with exhaustion and hopelessness. Like other shows of the time, Bojack Horseman or Rick and Morty, dealing with fatigue and despair are also thematically essential. However, where others conceal it behind humour or irony, Samurai Jack confronts this head-on, doubling down on the despair to set-up its ‘curriculum’ of hope. Its consistent message of disciplined search for meaning, precisely makes its teaching of hope more effective.

The concluding scene gives this lesson its final proof. In traditional superhero stories, most audiences expect that happy ending but Samurai Jack is nothing if not consistent. After Jack’s triumphant victory over Aku, he now loses Ashi as she cannot exist without Aku. He loses the one person who rekindled his hope and Samurai Jack refuses the audiences of that comfort, and Jack is thrown back into despair.

Jack loses Ashi at their wedding (left) and mourns her in an almost monochromatic backdrop (right)

Jack is reminded of Ashi from the ladybug (left) (see above) and his depressing world is restored with colour (right)

This time, instead of letting despair remain, he turns acceptance into the most mature form of hope, immortalising Ashi in his memory, carrying her through the rest of his life. This closing image completes the show’s pedagogy: despair will always remain, but one can always learn to live with it. For the generation that grew up with Jack in a world of increasing uncertainty and turmoil, Samurai Jack is an incredibly unexpected yet brilliant study of resilience and hope, making Samurai Jack the most unexpectedly realistic superhero today.

References:

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

Frankl, V. E. (1984).Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy (3rd ed.). Simon & Schuster. (Original work published 1959) https://archive.org/details/manssearchformea00fran_0/page/n9/mode/2up

Lev-Wiesel, R. (2008). Beyond survival: Growing out of childhood sexual abuse. In S. Joseph & P.A. Linley (Eds.), Trauma, recovery, and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress (pp. 145–160). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118269718.ch8

Milona, M. (2020). Philosophy of hope. In S. C. van den Heuvel (Ed.), Historical and multidisciplinary perspectives on hope (pp. 99–116). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46489-9_6

Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., & Sigmon, D. R. (2002). Hope theory: A member of the positive psychology family. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 257–276). Oxford University Press.

Tartakovsky, G. (Writer & Director). (2017). Samurai Jack: Season 5 [TV series]. Cartoon Network Studios / Williams Street.