Batman’s Symbolism of Hope in The Dark Knight (2008)

By: Malcolm Ng

Introduction

In Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (TDK) (2008), Gotham is shown as a city choking on crime, corruption, and despair, where hope feels scarce. The film frames its central conflict around three figures: Harvey Dent, the idealistic district attorney hailed as Gotham’s “White Knight”, Batman, the vigilante who enforces justice from the shadows, and the Joker, a force of chaos who seeks to dismantle Gotham’s fragile order. Commonly read as dual symbols of hope, Batman and Dent are staged by the film as partners, struggling against the Joker to restore Gotham from its near-apocalyptic collapse.

Harvey Dent's first meeting with the Batman

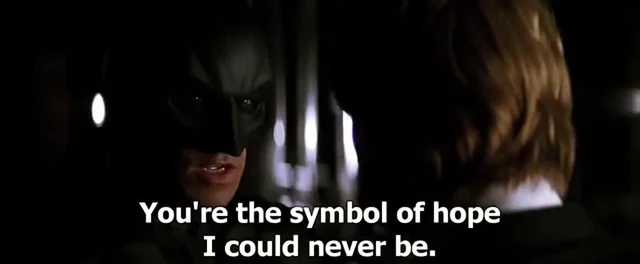

Even though widely regarded as a symbol of hope, TDK presents a conflict between the conventional definition of hope in Batman’s heroism and the common interpretation of Batman. Critics and casual movie-goers alike uphold this conventional reading. This will be further elaborated while trying to rationalise the reading of Batman’s symbolism. Within the film, however, Batman himself concedes to Dent, “You’re the symbol of hope that I could never be. Your stand against organised crime is the first legitimate ray of light in Gotham for decades… Gotham’s in your hands now.” This exchange suggests that Batman consciously hands over the public mantle of hope to Dent while assuming a darker, supporting role. This darker, supporting role relies on violence and intimidation to dismantle criminal operations and deter further chaos, as opposed to Dent’s vision of legitimacy and institutional change to instil hope. Therefore, I argue that TDK’s Batman deviates from its standard interpretation and redefines hope in heroism by presenting a version of it built not on inspiring the citizens of Gotham, but on inducing fear and intimidation within perpetrators.

Batman conceding to Dent on Gotham's future. (Image from u/ScoreImaginary5254, 2024, r/batman, linked here)

To examine this contradiction, this essay will reference Milano’s (2020) exploration of concepts of hope and Bosch’s (2016) concept of heroism in a post-9/11 setting. “The Standard Account” of hope in Milano (p. 2) explains the rationale behind Batman’s conventional association with hope, along with Dent’s version of hope. Secondly, the “Third Factor” filling in the gaps between belief, desire and hope is used to account the other possible ways hope arises or can be expressed. More specifically, the way TDK’s Batman acts as a symbol of hope through fear and intimidation instead. Lastly, the “Third Factor” of “Perceptual Theory” accounts for the way Batman justifies the need to preserve whatever illusion of hope remains once Dent’s idealism collapses, even at the cost of his own reputation, given that even the most legitimate hero can turn violent. This would then explain how hope can present itself in different forms over time within Batman, based on the situation he’s forced into, which brings Batman out of the conventional “Standard Account” of hope that he’s known for, at least in the context of TDK.

The Popular Consensus – Batman as a Symbol of Hope

Across popular discussions and fan communities, Batman is widely regarded as Gotham’s symbol of hope, with his commitment to eradicating criminality within Gotham, no matter how impossible it may seem. Threads on platforms such as Reddit’s r/batman repeatedly describe Batman as someone who “has always been a symbol of hope” or “is the dark symbol of hope.” Critics like Barkman (2023) and Johnson (2014) also echo this same sentiment of hope in Batman. Barkman describes Batman as a “symbol of justice, incorruptibility, and hope,” suggesting that anyone can embody what Batman represents by consciously choosing to uphold justice and work towards a brighter, crime-free Gotham (p. 8). This aligns with Johnson’s view that “only Batman is willing to consistently believe in a brighter future in Gotham”, constantly choosing to fight for a better Gotham while fending off its worst criminals (p. 14). Both scholars thus support the interpretation that Batman embodies hope, whether as a personal conviction or as a symbol for others. This public consensus also reflects the cultural expectation that Batman, by his very existence, should inspire hope and the moral courage to strive for a better society. Besides examining what fans and critics have to say, analysing how the general perception of hope arises and operates while drawing connections to TDK’s Batman would also serve as a means to understand how such an impression of Batman comes about.

Philosopher Michael Milona (2020) offers a framework for the common understanding of Batman as a symbol of hope through what he terms the “standard account of hope”. In this account, hope consists of two components, namely a desire for a particular outcome and a belief that this outcome is possible, even if uncertain (p. 100). Through this lens, Batman’s desire for Gotham’s redemption pushes him to persevere in his belief for a better Gotham despite the unlikeliness of it due to Gotham’s endless corruption, precisely embodying this account of hope. The Bat-Signal, shining against Gotham’s skyline, becomes a visual expression of this belief. It encourages citizens to believe in the possibility of their own safety even when despair and danger seem inevitable. Likewise, the group of copycat vigilantes who don Batman’s image to confront criminals reflects this same dynamic. Their imitation signifies the internalisation of Batman’s belief that Gotham can still be saved, which shows the desire and a faint belief that change is possible. Some might argue that these imitations trivialise Batman’s mission, showing recklessness rather than inspiration. Even then, this misguided imitation of Batman’s vigilante antics demonstrates the contagious nature of hope, which Milona describes as a fragile but motivating blend of desire and belief that still moves people to act. Therefore, through such imagery, TDK showcases the way symbols of endurance can transform personal convictions of Batman into a form of morality that the collective people of Gotham can adopt and drive change in their own way, grounding Batman’s conventional interpretation as Gotham’s symbol of hope through inspiration.

The Bat-Signal in action

Hope – Inspiration versus Fear and Deterrence

With the popular consensus of Batman’s embodiment of hope through inspiration in mind, TDK complicates this perception by portraying a different way Batman embodies hope, through fear and deterrence instead. His first appearance in the film immediately establishes this tone with the tense opening montage and having low-level criminals whisper about whether “the Bat” is out tonight. When one of them catches sight of the beam of the Bat-signal in the sky, he freezes in panic, abandoning his crime before it even happens. A few scenes later, Batman emerges from the shadows to bust a drug deal, attacking both mobsters and Scarecrow’s henchmen with brutal efficiency. These sequences make clear that his symbolism of hope comes less from a place of inspiration than from that of deterrence. Even citizens who idolise him misunderstand what he stands for, where ordinary citizens in makeshift Batman costumes attempt to copy his vigilantism, wielding shotguns and wearing hockey pads. When Batman silences them with “I don’t wear hockey pads,” he explicitly disapproves of their imitation not to disown hope, but to redefine it. Thus, TDK’s portrayal of Batman suggests that Gotham’s faith in him depends on his method of deterrence and not inspiration, which Milona would describe as a third form of hope that arises from fear itself. Rather than inspiring virtue directly, Batman’s deterrent presence aims to construct and maintain societal order through intimidation, which, as Bosch later theorises, reveals the effectiveness of fear in preserving social stability and thereby giving hope to Gotham.

This alternate interpretation of heroism reflects what Bosch terms the “politics of threat” in post-9/11 popular culture, where social order is maintained not through trust or inspiration but through the strategic use of fear. Batman’s symbolic power lies in deterrence, which echoes Bosch’s concept of maintaining social order through spreading paranoia and fear, where the threat of punishment becomes the city’s assurance of safety. Yet through Milona’s concept of the “third factor” (p. 102), this fear does not negate hope but offers another way of interpreting it. According to Milona’s framework, the third factor of hope emerges not from denying despair, contrary to the belief that to despair is to be without hope (p. 102), but from reconciling despair and hope. This is done by transforming anxiety into the very concept that sustains belief. Within this logic, Bosch’s politics of threat can be understood as another possible factor within Milona’s concepts of the third factor, namely fear, which, when harnessed and directed, becomes a source for hope. Batman’s deterrent fear then functions as an alternate form of hope through the belief that discipline, consequence, and vigilance can uphold moral order when inspiration alone falters. In contrast, district attorney Harvey Dent channels a more conventional form of hope grounded in transparency and law, assuring Gotham that “the night is darkest just before the dawn.”, as per Milano’s standard account of hope. Nolan’s juxtaposition of the two, Batman’s shadowed hope and Dent’s luminous one, suggests that Gotham’s source of hope depends not on the eradication of fear but on its transformation into a sustaining force for order.

Batman confronting his mimics and Scarecrow's crew

Batman’s Heroism as Scaffold for Dent’s Symbol of Hope

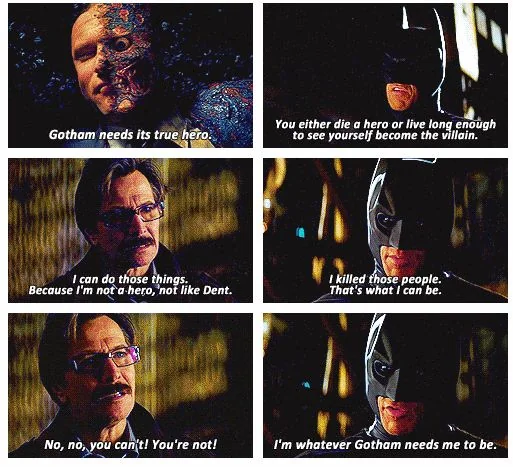

In the final act, Gotham’s faith in moral order collapses, which then forces Batman to sustain hope not by embodying inspiration but by weaponising fear in service of the belief that Dent was the “White Knight” that everyone thought him to be and that his hope remains pure and uncorrupted. The Joker’s victory comes through the successful corruption of Harvey Dent, Gotham’s public emblem of lawful hope, into a murderer driven by vengeance. When Dent dies after threatening Gordon’s family, Batman recognises that Gotham’s visible ideal of justice has perished. Exposing that truth would confirm the Joker’s conviction that every moral ideal decays under chaos, destroying all shred of hope Gotham had harboured when Dent inspired them to believe in a brighter future. To prevent that collapse, Batman tells Gordon, “Sometimes the truth isn’t good enough. Sometimes people deserve to have their faith rewarded.” His choice reframes justice as the preservation of hope by taking responsibility for Dent’s crimes, and in doing so sustains the illusion that civic virtue endures.

Batman's conversation with Gordon on taking the rap for Dent's death. (Image from u/TORONTOnative-, 2024, r/batman, linked here)

However, Batman’s lie also perfects his own symbolic transformation. Through Bosch’s line of argument that social stability necessitates fear through vigilance and violence, his willingness to be feared becomes the stabilising force of order. Through Milona’s third factor of hope, that same fear is transmuted into the resilience of Gotham in believing in a better future. Publicly condemned, Batman doubles down on his role as Gotham’s source of deterrent hope. His darkness becomes the scaffold that upholds Dent’s luminous idealism of hope for a better Gotham through the possibility of change within legitimised channels of legislation. Nolan’s closing sequence visualises this synthesis as the camera follows Batman into the darkness while police lights flare behind him like remnants of faith. Gordon’s final words of “He’s the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it needs right now”, seal this union of opposites. Hope, as the film suggests, survives only when fear bears its weight.

Batman riding off into the night as the police chases after him, under the suspicion of killing Dent

Conclusion

Nolan’s TDK ultimately redefines the relationship of hope in heroism, between inspiration and fear. What begins as a struggle between two competing symbols of Dent’s civic hope and Batman’s shadowed deterrence culminates in their fusion. Through Bosch’s politics of threat, fear becomes Gotham’s mechanism of moral regulation. Through Milona’s third factor of hope, that same fear is reconciled with belief to create endurance in despair. Batman’s final act transforms him from an emblem of intimidation into the invisible architecture of Gotham’s faith. His self-sacrifice sustains the illusion that goodness can survive, even when truth would destroy it. TDK therefore suggests that hope, in an age of disillusionment, no longer thrives in purity or idealism but depends on the very darkness that threatens it. In becoming both the source of fear and the guardian of faith, Batman emerges not as the embodiment of hope, but as its necessary shadow, showing that hope can persist in both the form of inspiration and in the form of fear and intimidation.

References

Barkman, A., & Korvemaker, A. (2023). Christopher Nolan’s Joker as a consistent naturalist (and that’s still a bad thing). Religions, 14(12), Article 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121535

Bosch, B. (2016). “Why so serious?” Threat, authoritarianism, and depictions of crime, law, and order in Batman films. Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society, 17(1), 37–54. https://ccjls.scholasticahq.com/article/635

Milona, M. (2020). The philosophy of hope. In S. C. van den Heuvel (Ed.), Historical and multidisciplinary perspectives on hope (pp. 99–116). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-46489-9_6

Nolan, C. (Director). (2008). The dark knight [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures; Legendary Pictures.