by Tan Yu Xuan

Introduction

Interstellar (Nolan, 2014) has attracted scholarly interpretation for spiritual (Koh, 2016) and biblical (Chung, 2016) readings. But they overlook a crucial twist that seems to undercut spiritual readings. On the other hand, despite its scientific focus, Interstellar romanticizes faith. This paradox calls for an integrative framework that accounts for both the film’s apparent spirituality and its secular revelation. I propose reading Interstellar through Martin Hägglund’s This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom (2019), offering a holistic interpretation of the film’s seemingly conflicting elements. Its science-fiction setting heightens the sense of finitude, an essential part of Hägglund’s philosophy. Through this reading, we understand that faith is not exclusively religious but also essential to secular life. This explains why, even as Interstellar challenges religious frameworks, it still affirms the value of faith. The film also demonstrates Hägglund’s idea about the motivational force that arises from recognizing one’s finitude—a force expressed through commitment, sacrifice, and the desire to persist in memory beyond one’s limited lifespan.

Spirituality and Religiosity in Interstellar

Set against the backdrop of an impending ecological collapse, Interstellar follows Cooper, a former NASA pilot tasked with traveling into space to find a habitable planet to replace Earth. Spiritual metaphors are established from the outset, despite the film’s scientific worldview. The story begins when his daughter, Murph, discovers strange dust patterns in her room that form coordinates, leading Cooper to a secret NASA facility headed by Professor Brand. Murph interprets this gravitational anomaly as the work of a “ghost,” a metaphor that recurs throughout the film.

Interstellar also employs biblical metaphor. At NASA, Professor Brand reveals that mysterious higher-dimensional “Beings” have placed a wormhole granting access to twelve potentially habitable planets. Of the twelve astronauts sent to explore them, three—Miller, Mann, and Edmunds—report promising data. The Beings, along with the symbolic number twelve, evoke divine guidance and recall the twelve apostles.

Professor Brand outlines two plans to save humanity: Plan A, which involves evacuating Earth’s population, and Plan B, which relies on stored embryos to start a new colony on another planet. Persuading Cooper to pilot the spacecraft Endurance, Brand assures him that Plan A is the priority and that he will solve the gravity equation—uniting gravity and quantum mechanics—to allow humanity to manipulate gravity, build a space station, and escape a dying Earth.

Despite Murph’s anger, Cooper departs, promising to return when she reaches his age. The crew first visits Miller’s planet, only to find it uninhabitable. They then choose to visit Mann’s planet over Edmund’s, despite objections from Amelia, the crew physicist and Professor Brand’s daughter, as Edmund had been her lover.

Meanwhile, Murph grows up to assist Professor Brand, who, before dying, reveals that Plan A was never feasible—the necessary data could only be obtained from inside a black hole. On Mann’s planet, the crew discovers that Mann falsified data to lure rescuers. After a fatal confrontation that damages the Endurance, Cooper sacrifices himself by plunging into the black hole so Amelia can reach Edmunds’ planet. Inside, he enters a five-dimensional tesseract created by the Beings, where he perceives every moment in Murph’s room. He transmits the missing data of the black hole through Morse code via the watch he gave her during their farewell, trusting their bond will lead her back to it. This allows Murph to solve the equation and save humanity.

As one might see, Interstellar has spiritual and biblical themes beyond its scientific surface. Koh (2016) argues that the film’s metaphors of ghosts and Beings, along with Amelia’s faith in love when defending Edmund’s planet, demonstrate the film’s use of “magic,” defined as “a ritualized form of optimism that connects individuals to a higher power.” Chung (2016) sees Cooper as a Christ-like figure whose sacrifice echoes Christian teachings of love, guiding humanity toward salvation. Sun (n.d.), however, argues it is anthropocentric love—the bond between humans—that counters the apocalypse.

Yet Koh and Chung overlook a crucial revelation: at the film’s end, Cooper realizes that the “ghost” is himself, manipulating gravity in Murph’s bedroom from the tesseract across time and space, and the Beings are future humans with advanced technology. This undercuts the idea of guidance from a higher power. Yet, Interstellar rewards faith—despite its contrast with science—as Edmund’s planet proves habitable and the bond between Murph and Cooper ultimately saves humanity.

Martin Hägglund’s This Life

The gap mentioned above calls for an integrative reading, and Martin Hägglund’s This Life, which examines faith and love across secular and religious contexts, provides an ideal lens. For Hägglund, faith is not exclusively religious; sustaining a secular life also requires it. This framework helps illuminate the interplay in Interstellar between its secular message and its romanticization of faith.

Hägglund (2019) observes that all forms of love, devotion, and commitment are inherently temporary, sustained only through constant dedication of future generations. Hence, one is finite in two primary ways: mortality and dependence on others (2019). He advocates “secular faith”—a commitment grounded in accepting life’s finitude while still affirming that lives are worth living. It is “faith” because the conviction to love life despite suffering cannot be proven through logic (pp.45-46). It is precisely because we care that it makes finitude such a pain (pp.45-46).

Hägglund (2019) identifies three dynamics of secular faith. The first is the belief that life is worth living, which goes beyond self-preservation and motivates even altruistic acts. Self-sacrifice is not disbelief in one’s own life, but faith that the cause or person one serves holds equal or greater value. The second dynamic is that secular faith is a necessary uncertainty. Commitment requires us to have faith in others and the future, despite the risk of disappointment, betrayal, or failure. The third is that finitude itself is the source of motivation. It is the realisation of our finitude that creates urgency to love and act. In this essay, this motivational force to commit beyond our mortal life will be termed as the “infinite”—born from the realization of finitude.

In contrast, religious faith devalues finitude, as it seeks salvation from eternity (Hägglund, 2019). He argues that the religious view of eternity removes urgency—if nothing can be lost, then nothing can truly be valued or loved.

Finitude in Interstellar

The apocalyptic setting in Interstellar and the presence of time dilation serve to heighten the sense of finitude.

Time dilation—the phenomenon where time passes at different rates depending on gravitational fields or velocity—vividly dramatizes the finitude of love, intensifying its pain beyond ordinary experience. When Cooper and his team spend just a few hours on Miller’s planet, twenty-three years pass on Earth. Cooper is left facing recorded messages from Murph, a childhood he can never reclaim. These moments illustrate Hägglund’s concept of inevitable finitude. Cooper’s anguish demonstrates that, as Hägglund (2019) argues, it is precisely because he loves that the limits of time are felt so painfully.

(screen capture from Christopher Nolan, 2014, Interstellar, Paramount Pictures)

The film’s apocalyptic backdrop underscores life’s ultimate finitude and reinforces its secular message—that secular faith, not religious faith, drives humanity’s will to survive. Hägglund (2019, p.11) notes that “the most fundamental example of finitude” is that “earth itself will be destroyed.” Religious faith would not struggle to preserve humanity in such a crisis, since many see the world’s end as salvation rather than tragedy (p.55). In contrast, secular faith insists on saving humanity, because the very first dynamic of secular faith is a belief that life is worth living despite its finitude (Hägglund 2019). It should be noted that Hägglund does not claim that all religion fails to care for humanity; rather, he invites religious believers who emphasize the here and now and the caring of secular life to examine what truly shapes their belief. As he argues, “if you care for our form of life as an end in itself, you are acting on the basis of secular faith, even if you claim to be religious” (Hägglund, 2019, p.13). Hägglund (2019) argues that awareness of finitude drives us to preserve what is precious. In Interstellar, when Professor Brand recites Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” (1951) as the crew departs, this drive to preserve operates on a larger scale: the desire to save humanity itself. Written for a dying father, the poem pleads for resistance against death and preservation of life—however brief—contrasting sharply with religious faith, which often treats death as a release into eternity rather than a loss to be resisted.

The film also explores another facet of finitude: the dependence on others. The Endurance mission rests on faith that the twelve astronauts would report truthfully on their planets’ habitability—a trust shattered by Dr. Mann’s deceit. Similarly, the crew’s sacrifices hinge on belief in Dr. Brand’s promise to solve the gravity equation, which later proves false. Yet despite these betrayals, Interstellar affirms the second dynamic of secular faith: that commitment—to a cause or a person—inevitably requires trust in others. The film romanticizes this aspect of secular faith, even at the expense of scientific logic. Cooper’s transmission of data through the black hole relies on his belief that Murph’s love will lead her to the watch he gave her during their farewell—a faith that ultimately proves true. Similarly, Amelia’s unwavering belief in Edmunds’ planet is proven to be correct in the end as it is the only habitable planet. Her speech:

Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space. Maybe we should trust that, even if we can’t understand it.

This shows an embodiment of secular faith: Love and faith are inseparable, that we commit to it despite our ability to logically deduce it.

The Infinite within the Finite

The infiniteness of love arises from the motivational force of its intrinsic finitude. Hägglund (2019, p.16) wrote that the awareness of death (finitude) creates the very motivation to dedicate our lives meaningfully (infiniteness); without finitude, there would be no commitment. This idea is exemplified by Dr. Mann’s remark:

You know why we couldn’t just send machines on these missions, don’t you? A machine doesn’t improvise well because we can’t program a fear of death. Our survival is our single greatest source of inspiration.

Humans are irreplaceable because, unlike unconscious machines, their vulnerability to death drives them to act. Hägglund (2019) argues that the risk of loss creates urgency, which demands action. Interstellar is permeated by this urgency: Brand and Murph race against time to solve the gravity equation before Earth becomes uninhabitable, Cooper desperately longs to return to Murph.

The first dynamic of secular faith shows that one can value life not just for oneself but for others, even to the point of extreme altruism (Hägglund, 2019). From this perspective, the numerous sacrifices in Interstellar is to show the infiniteness of finite love. This explains the twelve astronauts’ one-way missions, undertaken with the knowledge that an uninhabitable planet would mean certain death, as well as Cooper’s own self-sacrifice when he enters the black hole. Hägglund (2019, p. 55) argues that the motivational force of finitude includes the desire to continue to “exist” through leaving legacies in meaningful causes or the rearing of children. The astronauts’ sacrifice reflects a desire for the greater cause of humanities’ survival to endure beyond their finite lives. Cooper’s motivation is similarly rooted in love for his child and the desire for her to live beyond his own life. Initially reluctant to leave her, he is persuaded when Brand emphasizes the urgency of her finitude: “…your daughter’s generation will be the last to survive on Earth.” Recognizing that failure of Plan A would doom all—including Murph—Cooper ultimately sacrifices himself, valuing the survival of others above his own life. While Chung (2016) reads Cooper’s sacrifice as a Christian allegory reflecting Christ’s love, I argue that the film instead portrays the infiniteness of love. The religious trope is to show that love that arose through secular faith can drive even the most altruistic actions, comparable to Christ’s sacrifice.

The secular message is further emphasized through the film’s critique of the “Beings.” How Interstellar portrays the Beings resembles the infiniteness of love due to our intrinsic finitude of experiencing time. At first, these beings—capable of transcending time and space—seem akin to divine saviors. Koh (2016) notes that the Beings who place the wormhole for humans are “analogous to a benevolent and loving God.” However, the tesseract sequence later showcases a critique of such a higher being. Responding to Taylor’s description of God—“all times are present to him, and he holds them in his extended simultaneity. His now contains all time”—Hägglund argues if time is experienced simultaneously in an instance, happiness of a precious moment that is built on shared memory can never be experienced, as it “deprives us of a past and a future.” (Hägglund, 2019, pp.52-53) The Beings in Interstellar mirrors Taylor’s God, experiencing time simultaneously. Cooper realizes this in the tesseract:

All of this is one little girl’s bedroom. Every moment, it’s infinitely complex. They have access to infinite time and space, but they’re not bound by anything!

Cooper succeeds where the Beings fail because his finitude allows him to experience love through a linear network of past and future, enabling him to locate the watch and recognize its emotional significance.

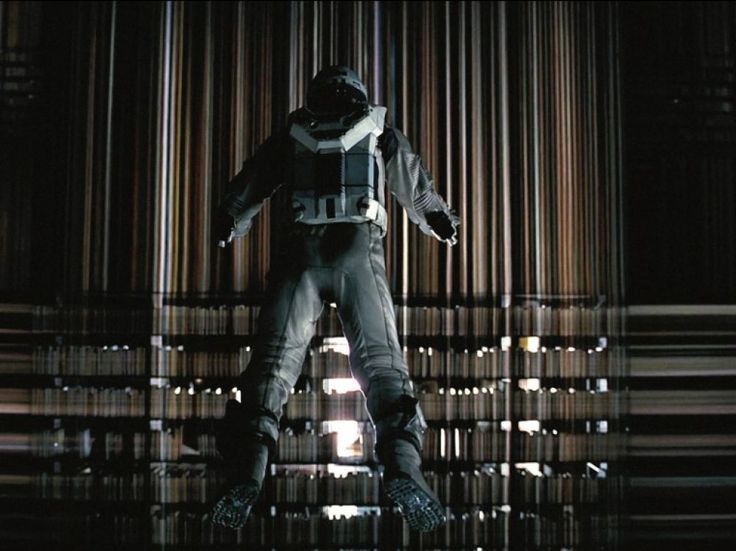

(screen capture from Christopher Nolan, 2014, Interstellar, Paramount Pictures)

The secular message is further reinforced when Cooper reveals the Beings’ true identity:

They’re not ‘Beings’, they’re us…No, no, not yet, but one day, not you and me, but people, a civilization that’s evolved past the four dimensions we know.

The twist—that the Beings are actually future humans—rejects religious faith: salvation does not come from an external divine power, but from humanity itself.

Another crucial motif for understanding the infiniteness of love is the spiritual metaphor of the “ghost.” Hägglund (2019, p.158) observes that in face of death, we prolong the existence of our loved ones in our memory, while also realising that our own existence relies on being remembered by future generations. This yearning to remember and be remembered is the infiniteness of love expressed through the ghost motif. Cooper introduces the ghost metaphorically in his farewell to Murph:

Your mom once said something I never quite understood. She said, ‘Now we’re just here to be memories for our kids.’ … Once you’re a parent, you’re the ghost of your children’s future.

Here, the haunting in Murph’s room—falling books and dust patterns—visualizes a parent’s desire to continue living within their children’s memories, as it is revealed that the “ghost” is Cooper himself, trying to reach Murph across time and space from within the tesseract. The ghost also signifies the living’s urge to preserve the imprints of those who have left, refusing to forget. This is reflected in Cooper’s son, Tom’s stubborn refusal to leave the family farm even when the dust storm has worsened his family’ health, because he promises Cooper to look after it. The infiniteness of love lies in Cooper’s enduring influence: though his time with his children is brief, his presence persists as a “ghost” watching over them, even amid the trauma reflected in Murph’s anguished shout to Tom, “Dad just abandoned us!”

Conclusion

I propose reading Interstellar through Martin Hägglund’s This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom (2019), which reconceives faith and love in purely secular terms. Through this lens, Interstellar emerges not as a religious parable but as a meditation on secular faith—a faith to commit to mortal life despite its finitude. Interstellar’s apocalyptic backdrop amplifies the sense of finitude, which motivates love and action—a persistent idea in Hägglund’s philosophy that finitude is the foundation of care.

References

Chung, C.-Y. (2016). Love as the element that transcends space and time in Interstellar. International Journal of Research, 3(9), 637–639. https://journals.pen2print.org/index.php/ijr/article/view/4494/4323

Hägglund, M. (2019). This life: Secular faith and spiritual freedom. Pantheon Books.

Koh, J. (2016). A fantasy in sci-fi’s clothing: Interstellar and the liberation of magic from genre. Re:Search: The Undergraduate Literary Criticism Journal, 3(1), 39–55. https://ugresearchjournals.illinois.edu/index.php/ujlc/article/view/174/144

Nolan, C. (Director). (2014). Interstellar [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

Sun, R. (n.d.). Love, gender and anthropocentrism in The Wandering Earth, Interstellarand Avarya. Department of Cultural and Religious Studies, City University of Hong Kong. https://www2.crs.cuhk.edu.hk/f/page/312/4063/Good_Paper_SUN_Ruigang.pdf