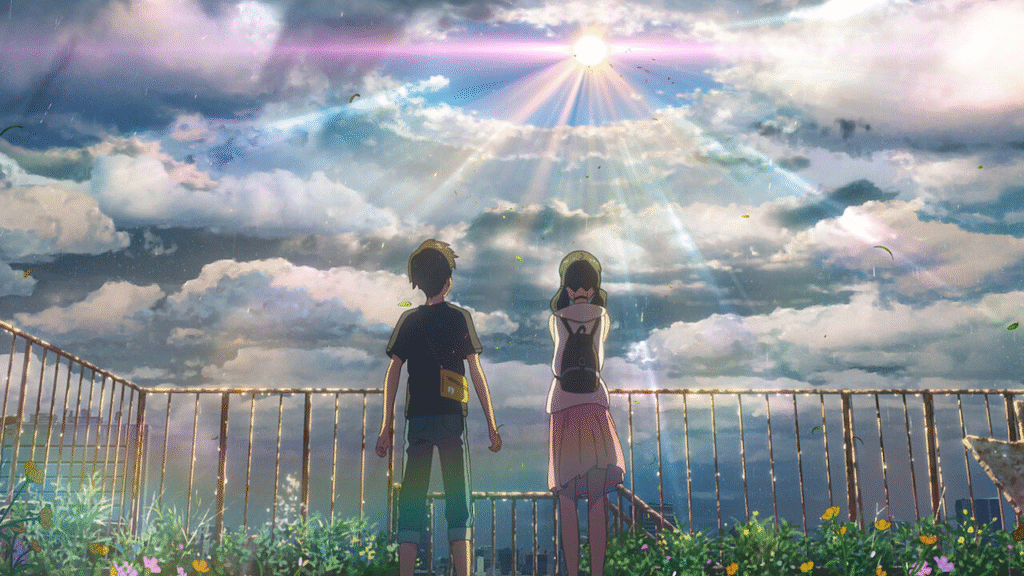

“Who cares if we don’t see the sun shine ever again? I want you more than any blue sky.” – Hodaka, Weathering with You

by Cerys Leck

In many representations of Japanese culture, the philosophy of messhi hōkō (self-sacrifice for the sake of the group) is depicted as a prized ideal, due to the sacrosanct principle of prioritising the group over the individual to maintain harmony, also known as wa (Kawaguchi, 2024). In contrast, selfishness—seen as a departure from this norm—is often considered morally questionable. Yet, Makoto Shinkai’s animated film Weathering with You (2019) disrupts the cultural script: instead of affirming the nobility of self-sacrifice, Shinkai presents an inversion. In Weathering with You, during the summer of 2021, Tokyo is plagued by relentless rainfall, and the film follows a pair of lovers: Hodaka, a runaway teenager, and Hina, a girl gifted with the supernatural ability to bring sunshine. However, when Hina finds out that her existence on Earth is causing Tokyo’s abnormal weather, Hina sacrifices herself, ascending into the sky to restore nature’s balance. Hodaka, devastated by Hina’s disappearance, selfishly chooses to save her by bringing her back to Earth, but his display of selfish love precipitates the catastrophic flooding of Tokyo. Hence, while the film disrupts the cultural script, Hodaka’s decision also invites reflection on love in the apocalypse—should love supersede collective duty? This article argues that Weathering with You renounces Japan’s cultural practice of messhi hōkō by justifying the prioritisation of one’s personal interests—love—even at the cost of collective wellbeing. Hence, the article will explore how Weathering with You navigates this moral dilemma, where I further argue that Hodaka’s subversion of messhi hōkō is warranted due to his exceptional duty as a lover to Hina. This will be elaborated upon by invoking Agamben’s State of Exception and Horn’s theory of teleological particularism.

The Cultural Script: messhi hōkō

The philosophy of messhi hōkō is a deeply ingrained societal culture of self-sacrifice for the collective that shapes individual behaviour, due to its continued institutional reinforcement. In Masao Miyamoto’s Straitjacket Society: An Insider’s Irreverent View of Bureaucratic Japan (1994), this deep-rooted culture is attributed to its ubiquity across social institutions, as messhi hōkō is first instilled in children through the education system as a moral expectation and later reinforced in the workplace as a professional obligation (pp. 21–22). This institutionalisation of messhi hōkō reveals how deeply the ideal of self-sacrifice permeates Japanese social consciousness.

Surprisingly (or unsurprisingly), the first half of Weathering with You reproduces this cultural ideal of messhi hōkō, as seen from Hina’s self-sacrifice. In the film, although Hina’s supernatural abilities allow her to temporarily clear the torrential rain in Tokyo through prayer, it results in her gradual disappearance, making her actions an embodiment of self-sacrifice for the collective. This final act of self-sacrifice is seen when the storms worsen and Tokyo experiences snow during summer, prompting Hina to recognise her responsibility as the “weather maiden”. To restore the weather’s balance, Hina sacrifices herself by allowing her body to ascend into the clouds, effectively ceasing to exist on Earth and clearing the skies (Shinkai, 2019). Thus, Hina’s decision to sacrifice herself underscores the pervasiveness of messhi hōkō in Japanese society, where the societal expectation is so strong that it affects one’s behaviour, even when it means one’s demise.

Unlike Hina, Hodaka chooses to defy the philosophy of messhi hōkō. He prioritises his personal connection with Hina over the collective good of Tokyo and reverses her act of self-sacrifice. In the film, Hodaka runs through the torii gate to enter the realm Hina is in—a liminal space between the human and divine world—encouraging her to return with him to Earth (Shinkai, 2019). After they fall through the clouds together, the city of Tokyo begins to rain heavily again, signalling Hodaka’s reversal of Hina’s self-sacrifice.

While the film does not elaborate on Hina’s response to Hodaka’s decision, her acceptance of Hodaka’s plea to return with him underscores the film’s emphasis on personal relations over the collective. This tension between individual love and collective responsibility thus forms the central ethical dilemma of the film, which invites further examination of whether Hodaka’s defiance can be morally justified.

Breaking the Cycle

The catastrophic weather that engulfs Tokyo in Weathering with You signals an environmental collapse, giving the film an apocalyptic backdrop that justifies Hodaka’s cultural transgression of messhi hōkō. The disastrous setting of the apocalypse tends to be unkind to the society it befalls, causing greater fragility in the psyche and social fabric of society (Škrovan, 2024, p. 118). The apocalyptic setting also rids any semblance of normalcy as social norms and customs collapse, creating a space wherein new configurations of society may emerge (Toone, 2015), such as Hodaka’s seemingly immoral decision to save Hina.

This notion of a suspension of order during catastrophe parallels Giorgio Agamben’s concept of the state of exception, which can be extrapolated to the setting of Weathering with You. Agamben discusses how this setting is one in which law and order are temporarily suspended due to a crisis, such as war, allowing sovereign powers to exercise greater authority (Agamben, 2008). Although Agamben’s State of Exception is traditionally used to understand a nation’s sovereignty through a political and legal lens, I still view that its conceptual reach extends beyond governance to illuminate broader questions regarding human agency and decision-making in exceptional circumstances, making it an apt analytical framework for analysing how the apocalyptic setting of Weathering with You may have contributed to Hodaka’s decision.

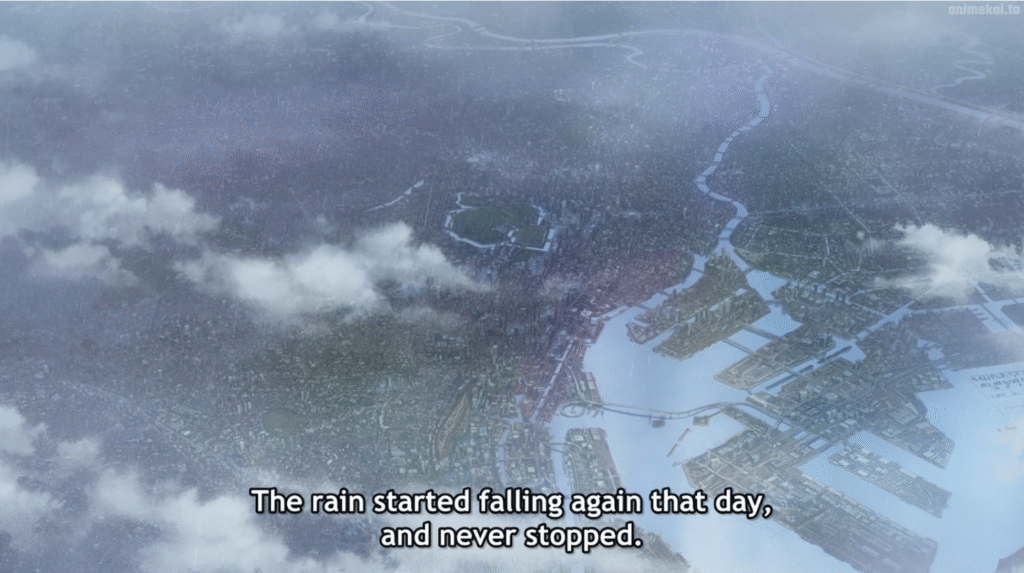

The apocalyptic setting of Weathering with You operates as what Agamben would recognise as a literalised state of exception, thus making Hodaka’s climactic decision both comprehensible and necessary. To understand why Hodaka’s decision may be justified, we first need to examine the response of institutions during the state of exception, which is the sacrificial system of “weather maidens”. As Agamben (2008) argues, necessity in the state of exception permits acts that would typically be considered unlawful to become justifiable and essential responses under crisis (pp. 24–26). Hence, the sacrificial system of the “weather maiden” invokes necessity to legitimise Hina’s sacrifice, as her sacrifice appears as the only means to restore meteorological normalcy and benefit the collective, thereby transforming what would constitute murder into a justified sacrifice. Crucially, Agamben (2008) also notes that necessity is “an entirely subjective” judgment (p. 30). Viewing the events of the film retrospectively, Hodaka’s decision to save Hina can be interpreted as invoking the subjectivity of necessity. This is because in the film, following the flooding of Tokyo, citizens manage to adapt to their circumstances: using boats as public transport, elevated walkways, and the ubiquitous use of umbrellas (Shinkai, 2019).

As the citizens of Tokyo adapt to catastrophe instead of overcoming it, “the state of exception has now become the rule” (2008, p. 9), as Agamben puts it, becoming a new normal of sorts. In such a condition, the ordinary logic of moral order—where individual sacrifice is valorised for the sake of the collective—loses its binding force. Therefore, Hodaka’s act of saving Hina demonstrates that her sacrifice was not a true condition for survival but a subjective decision set out by institutions that deemed her sacrifice necessary, and recognising this subjectivity thus validates Hodaka’s defiance of messhi hōkō through reversing Hina’s self-sacrifice.

Admittedly, one might argue that Hodaka’s decision cannot be justified retrospectively, since he could not have known whether reversing Hina’s sacrifice would condemn or spare Tokyo. Hence, this very uncertainty invites a different mode of evaluation—one that considers not the outcome, but Hodaka’s perception of necessity in that moment. I argue that Hodaka’s choice is morally defensible as his decision is grounded in the relational obligation towards Hina as a lover, which is best explained through Charles Horn’s theory of teleological particularism (Horn, 2024).1 Horn defines teleological particularism as a moral theory that maintains that an individual’s moral responsibilities are relative to one’s roles and duties in society, and hence moral principles are not universal but are subjective (2024, pp. 1751–1752). According to this view, “an agent is morally justified in their actions if and only if the action conforms with a role they occupy” (Horn, 2024, p. 1741). This is because roles we have in society typically constitute our identities, and roles are usually in relation to others, resulting in moral obligations to others. More crucially, in the apocalyptic context of meteorological catastrophe in Weathering with You, since traditional social structures have been dissolved (Škrovan, 2024, p. 118), these role-based obligations become more salient.

Throughout the film, Hodaka progressively assumes the role of Hina’s protector. While initially strangers, Hodaka first protects Hina when she is nearly forced into prostitution by intervening in the situation (Shinkai, 2019). Hodaka similarly protects Hina and her younger brother Nagi as the oldest of impoverished teens navigating the city of Tokyo together, recommending Hina leverage her supernatural powers for money through their “sunshine girl” business (Shinkai, 2019). By the film’s climax, Hodaka, Hina and Nagi resemble a family unit, with Hodaka proclaiming how “[he]’ll work, [he]’ll earn enough for all of [them]” (Shinkai, 2019), cementing his strong sense of responsibility towards their makeshift family. This relational configuration defines Hodaka’s particular telos: his duty to Hina arises from familial duty, where this role is constructed through shared experience and mutual dependence. To further complicate Hodaka’s duty to Hina beyond the familial role, Hodaka also functions as Hina’s romantic partner. The night before Hina sacrifices herself, Hodaka puts a ring on her ring finger and has her promise that “[They]’ll always be together” (Shinkai, 2019), emblematic of a promise made during matrimony. Hence, Hodaka’s role as a protector, which stems from both his familial duty and duty as a lover, carries specific moral demands: that Hodaka provide for Hina and prioritise her interests over the collective’s.

While Hodaka arguably also has the duty of prioritising societal welfare being a citizen of Japan, however, considering his social position as a runaway teenager, Hodaka has little moral obligation to the citizens of Tokyo. As a runaway, Hodaka’s relationship with the city of Tokyo is marked by detachment and alienation. Several times in the film, Hodaka repeats “Tokyo is scary” (Shinkai, 2019), revealing his experience of the city not as a community that includes him but as a hostile space that threatens him. Moreover, as a youth whom Tokyo’s authorities actively hunt, its social structures offer him no protection or belonging. Where Horn argues that “the more [e]mbedded we are in communities…the more obligations and responsibilities we have to others” (Horn, 2024, pp. 1751–1752), Hodaka represents the inverse, occupying virtually no role in society as a runaway. Hence, Hodaka’s moral responsibility towards Hina outweighs his duty towards the wider public of Tokyo, rendering his decision to save Hina morally defensible.

Finally, one might object that, regardless of Hodaka’s personal alienation from Tokyo, the sheer scale of collective harm—a flooded metropolis—renders his decision unjustifiable. Nonetheless, the film’s epilogue, which takes place three years after Hodaka’s monumental decision, dismantles this utilitarian objection by contextualising Tokyo’s floods, which permit Hodaka’s decision. Hodaka speaks to an elderly woman who offers a crucial historical perspective, detailing how “Until about 200 years ago, [Tokyo] used to be under the sea. It used to be a bay, until human beings and the weather changed it. So well… I think it has just gone back to how it used to be before” (Shinkai, 2019). Her framing transforms the atypical weather from unprecedented calamity into natural restoration, revealing that Tokyo’s existence above water was an artificial intervention requiring periodic human sacrifice. The film’s earlier references to numerous “weather maidens” who preceded Hina—each similarly sacrificed to maintain meteorological order—suggest that only this cyclical violence prevented Tokyo from reverting to its original submerged state (Shinkai, 2019). From this perspective, the film’s narrative supports that Hodaka’s decision to subvert the cultural script of messhi hōkō represents a somewhat heroic termination of a sacrificial system that demanded successive generations of young women die to sustain an unsustainable climate.

Conclusion

Weathering with You ultimately renounces Japan’s cultural philosophy of messhi hōkō by affirming that love ought to supersede collective duty. Through Agamben’s concept of necessity and Horn’s teleological particularism, we can understand how the film legitimises Hodaka’s supposed immoral decision as an ethically necessary act amidst crisis. More broadly, Weathering with You has redefined how morality can be interpreted in the rather collectivist society of Japan, suggesting that there is room for individuality and even selfish love to take precedence.

References

Agamben, G. (2008). State of exception. University of Chicago Press.

Horn, C. J. (2024).The Last of Us as moral philosophy: Teleological particularism and why Joel is not a villain. In D. A. Kowalski, C. Lay, & K. S. Engels (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of popular culture as philosophy (pp. 1741–1756). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24685-2_11

Kawaguchi, S. (2024). The effect of cultural norms on group decision-making in Japanese corporations. Frontiers in Management Science, 3(5), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.56397/FMS.2024.10.07

Miyamoto, M., & Miyamoto, M. (1994). Straitjacket society: An insider’s irreverent view of bureaucratic Japan (1st. ed.). Kodansha International.

Shinkai, M. (Director). (2019). Weathering with you [Film]. CoMix Wave Films.

Škrovan, A. (2024). The pursuit of harmony: Groups and communities in post-apocalyptic narratives. World Literature Studies, 16(4), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.31577/WLS.2024.16.4.9

Toone, M. M. (2015). The folks of the post-apocalypse: The Road, religion, and folklore studies. Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism, 8(2), 88–97. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion/vol8/iss2/13

- Horn develops teleological particularism through his analysis of Joel’s decision in The Last of Us, arguing that Joel’s morally controversial act of saving Ellie over humanity’s potential cure is justified by his particular duty of love and care toward her as a father figure.

↩︎