Angel Lim, November 2025

Introduction

Source material for the cult classic sci-fi film Blade Runner (1982), Philip Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) (henceforth referred to as DADES) is set in a post-apocalyptic world plagued by the fallout and ruins from a nuclear war, where most humans have emigrated to space colonies. The scattered few who remain on Earth consist of humans that are genetically ‘unsuitable’, unable to afford emigration, or have personal attachments to Earth. Technology has advanced to a point where humanoid robot servants are almost indistinguishable from humans, save for their distinct inability to feel empathy. The novel follows bounty hunter Rick Deckard, tasked to track down and terminate six rogue humanoids who have escaped their designated roles on Mars and hidden amongst other humans on Earth as illegal fugitives.

Very early in the novel (and where the novel’s focus deviates heavily from the film), the reader is introduced to the idea of Mercerism, a religion that appears to centre its faith on two key tenets: the belief in the prophet Wilbur Mercer—a Christ-like figure that believers are able to connect with through the use of an “empathy box”, and the ability to feel empathy as proof of a believer’s humanity. The “empathy box” transports the consciousness of all who are using it at that specific moment to a virtual ‘scene’, where Wilbur Mercer is portrayed to endlessly suffer as he ascends a barren hill while being struck by stones. Believers can then choose to ‘fuse’ with Mercer, where their consciousness is transported into Mercer’s body, allowing them to collectively ascend the hill and feel the pain of being struck by stones alongside their prophet and other believers. Undergoing this ‘fusion’ with Mercer in this joint experience of pain and suffering is seen as one of the ways to clearly demonstrate empathy, allowing them to distinctly differentiate themselves from the apathetic humanoid robots, who have “no ability to feel empath[y] for another life” (p. 29). The religion thus seems to preach empathy as the defining trait of humanity—becoming a recurring social tool throughout the novel as a way for Deckard and other humans to identify the humanoid robots and reinforce the fact that they are human. In this sense, suffering is presented merely as a trial to endure on the path toward achieving empathy—the ultimate proof of a believers’ humanity.

Yet as the novel unfolds, suffering, rather than empathy seems to emerge as the true marker of humanity. Beyond the belief in their prophet Wilbur Mercer and performing empathy, the act of enduring and sharing pain—though ‘fusion’ or otherwise—becomes the only remaining way that the scattered humans can authentically form connections with and identify each other. This is especially so as even after Mercerism is exposed as a hoax by the media personality Buster Friendly, its believers continue to ‘fuse’ with their fake prophet, clinging to the ritual of collective suffering despite knowing it is artificial. Hence, I argue that humans continue to perform Mercerist practices not because they believe in Wilbur Mercer nor the moral ideal of empathy as an end goal, but because they believe in the collective experience of suffering itself as the definitive trait of humanity. Mercerism not only reconfigures suffering from a temporary process to overcome into a permanent condition of belonging, but sustains faith through shared ritual even in the absence of authenticity, ultimately acting as the foundation upon which humanity recognises and identifies with itself.

Representations of Suffering in Religion

Suffering in religious contexts are typically portrayed as obstacles to overcome or escape from, with the ultimate promise and comfort of a better end. Mercerism, however, places its comfort in the proving of humanity through acts of suffering itself.

Many apocalyptic texts like DADES that were written during the cold war mirrored “redemptive societies”—belief systems that promised salvation, moral renewal, and continuity during times of crisis. People turned to faith as a way of managing visions of an increasingly bleak future, giving societies hope of a brighter future during times of nuclear unrest and uncertainty (Duara, 2001). For instance, Walter M. Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1960) portrayed Catholic monks as the preservers of human knowledge post-war, framing religion as humanity’s hope for cultural revival even after collapse. Similarly, films like On the Beach (1959) depicted survivors clinging to ritual and shared ideals of a continued afterlife before their ultimate nuclear demise. Religious “redemption” hence provided people with the capacity to feel optimistic about their situation, where the suffering that they have gone through will one day (be it as a mortal or in the afterlife) be “redeemed” with a better end.

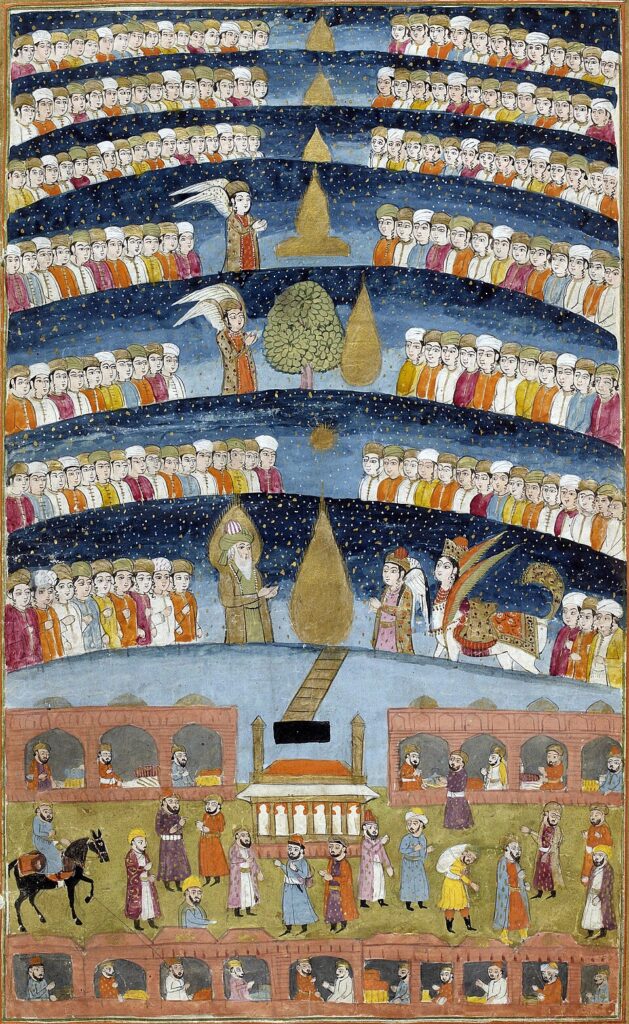

Similarly, processes of suffering in both eastern and western religions are often portrayed as an obstacle to overcome, performing as an intentional feature and soteriological tool towards a greater ultimate salvation or purification in the afterlife. In dominant western ideologies like Christianity, suffering is viewed as a necessary trial on the road to refine faith and grit, portrayed in Romans 5:4 where “suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope” (NRSVUE, 2021), showing that hope signifies a promise of salvation and eternal relief. Similarly, eastern religions like Buddhism and Hinduism conceptualise suffering (dukkha) as an inescapable step on the path towards enlightenment (nirvana), in which individuals have to renounce their need to control and their attachment over mortal possessions (Bratcher, 2019). Moreover, in Islam, suffering is framed as a test of faith and submission to divine will (sabr), and in Judaism, it can be seen as a tool for atonement with the hopes of being rewarded in the next life. This is to say that, despite theological differences, suffering in religion has consistently functioned as a demonstration of faith, fidelity, and resilience, serving as a process toward final salvation where suffering is ultimately relinquished—ultimately portraying suffering as a means rather than an end.

Mercerism’s portrayal of suffering thus appears, at first glance, to mirror the same structure of having an end goal of salvation through empathy. However, suffering in Mercerism, unlike established religions, offers no promise of ultimate respite or forgiveness. Its only “reward” is the confirmation that one is human precisely because one has empathy, to which the only way to prove empathy is through suffering. Hence, the act of suffering itself becomes the defining markers of humanity rather than moral or spiritual redemption.

Faith From Collective Experience

It is important to note that the faith and comfort of Mercerism stems not merely from acts of suffering itself, but from suffering as a collective. Émile Durkheim (1912) argues that religion is not defined by its gods or ideals, but by its capacity to generate ‘collective effervescence’—strong emotional and social bonds formed by common experience, shared meaning, and joint social rituals amongst humans, creating a sort of moral order and sense of solidarity (Durkheim, 1912). The ability to ‘fuse’ with Mercer and other humans regardless if believers are “…either here on Earth or on one of the colony planets” (p. 22) serves as an avenue for humans to foster connection despite their physical distance from each other in Earth’s desolate wasteland, hence allowing them a coping mechanism in the relief of a shared, empathetic human experience of suffering.

Late in the novel, Mercerism is exposed by television show Buster Friendly and His Friendly Friends as a hoax religion, where its prophet is nothing more than an actor called “Al Jarry” (p. 181). Though the purpose of perpetuating this false religion is never made clear, it is often inferred by readers as a rudimentary tool of social control and order for a scattered human population, repackaging ethical values such as caring for other lives under the umbrella term of ‘empathy’ (Sims, 2009). Yet, this revelation changes little—people like Deckard continue to ‘fuse’ with Mercer through their empathy boxes while actively cognisant of its artificiality. This reflects Jameson’s (2005) ‘critique of authenticity’ in Mercerism, where a manufactured system still ends up fulfilling genuine needs, hence remaining emotionally true (Jameson, 2005, pp. 366–370). The needs of the scattered human population for a collective order and moral ideal to abide by hence continues to be fulfilled by Mercerism regardless of its authenticity. The continuation of Mercerism as a collective experience beyond its fundamental tenets hence shows readers that religion does not depend on the existence of gods, but rather on the shared conviction and belief that suffering as a collective that binds people together.

Rituals of Suffering as an End in Mercerism

With suffering as a collective being the only organic truth remaining, the continuous rituals in which believers collectively suffer—such as the physical suffering through ‘fusion’ or the financial suffering of caring for animals—become the ultimate ‘end’ of Mercerism. Its rituals of suffering are not merely endured as trials, but actively embraced as sources of meaning and connection.

The ritualised process of believers sharing Wilbur Mercer’s pain as he is struck by stones produces a paradoxical sense of comfort, where participants willingly enter a shared state of suffering because it affirms their humanity and existence to others, “link[ing] [them] to everyone else who has ever fused” (p. 150). For isolated humans such as John Isadore who lives away from the few small physical communities that humans still have, fusion becomes the only way to seek belonging and validation. Through Mercer, Isidore is able to receive his reassurance that “[he is] not alone” (p. 25), even as a “chickenhead” (man with low IQ) that would by all means be ostracised by other humans.

The ownership and care of animals, whether genuine or electric, is another way that empathy is demonstrated in the novel. However, the emphasis on having an animal is not merely an act of compassion, but rather ritualised suffering through which humans bind themselves to economic commitments. For instance, Deckard’s decision to spend his entire bounty earnings on a Nubian goat—“the most expensive animal he could afford” (p. 146) shows Humans spend absurd amounts to display and feed their animals, all in a bid to signal their humanity to others. Phil Resch—a human whom Deckard initially suspects to be a humanoid—appears emotionally detached and unable to pass the “empathy test”, seemingly undermining empathy as Mercerism’s standard for humanity. Instead, the ultimate notion that proved him to be human was the fact that he “own[s] an animal; not a false one but the real thing” and that “[he] feeds it every goddamn morning” (p. 111). His participation in the collective suffering of animal-care proves sufficient to mark him as human. It remains the undefeated method of identifying the human collective, even as individual circumstances differ. Hence, Mercerism traps its adherents within a cycle where they must continually demonstrate their suffering in order to affirm their humanity. Suffering thus ceases to be a means to an end: it becomes the end.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the portrayal of collective suffering in DADES as the end goal of Mercerism is not fundamentally different from using empathy or salvation. By Durkheim’s view, religions fundamentally function as social institutions that allow humans to connect with each other, regardless of what the process to achieve that connection may be. This is especially pronounced in times of crisis (or in this case, a post-apocalyptic world), mirroring how religious and ritual practices provide a crucial source of hope where all other factors are uncertain or out of any individual’s control. The novel explores this nuance that the film largely sidelines, providing an alternative view for readers to think of what it means to be and ‘perform’ humanity through suffering.

References

Bratcher, S. (2019). Why do we suffer? Buddhism vs. Christianity. Reformed Perspective. https://reformedperspective.ca/why-do-we-suffer-buddhism-vs-christianity/

Dick, P. (1968). Do androids dream of electric sheep? Millennium.

Duara, P. (2001). The discourse of civilization and pan-Asianism. Journal of World History, 12(1), 99–130. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2001.0009

Durkheim, É. (1912). The elementary forms of religious life. Oxford University Press. https://monoskop.org/images/a/a2/Durkheim_Emile_The_Elementary_Forms_of_Religious_life_1995.pdf

Jameson, F. (2005). Archaeologies of the future. Verso. https://files.libcom.org/files/fredric-jameson-archaeologies-of-the-future-the-desire-called-utopia-and-other-science-fictions.pdf

New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition (NRSVUE). (2021). National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-Updated-Edition-NRSVue-Bible/

Sims, C. A. (2009). The dangers of individualism and the human relationship to technology in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Science Fiction Studies. https://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/107/sims107.htm?