Annie Du, November 2025

Introduction

In Joyce Carol Oates’ “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” set in 1960s suburban America, fifteen-year-old Connie is absorbed in her appearance, boys, and pop culture. Her mother criticizes her for being superficial, her father is emotionally absent, and Connie turns instead to the radio and the drive-in, where she briefly feels free and desired. One summer morning, when her family is away, Arnold Friend arrives at her house, presents himself as an older teenager, and invites her for a ride. His behaviour quickly turns sinister. When Connie resists, Arnold threatens her family and manipulates her with disturbingly intimate knowledge of her life, until she walks toward him in a trance-like state (Oates, 1966/2005, p. 388).

A popular interpretation of the story reads it as a cautionary tale warning young women about the dangers of chasing maturity and independence too early, as Connie is supposedly punished for seeking adult experiences before she is ready (Cougill, 2019). This reading, however, both misrepresents how the plot works and ignores the existential questions embedded in the title. Rather than a morality lesson about bad choices, the story invites a Christian-apocalyptic lens that, contrary to traditional Christian teleology, reveals a teenager’s failed attempt to find belonging and purpose. The influence of the Danish Christian existentialist Søren Kierkegaard and the Czech modernist Franz Kafka on Oates’ thinking clarifies the apocalyptic truth the story exposes: one may never find answers to the questions “Where are you going?” and “Where have you been?” by treating pop culture as a kind of religion, as Connie does.

Not a Cautionary Tale

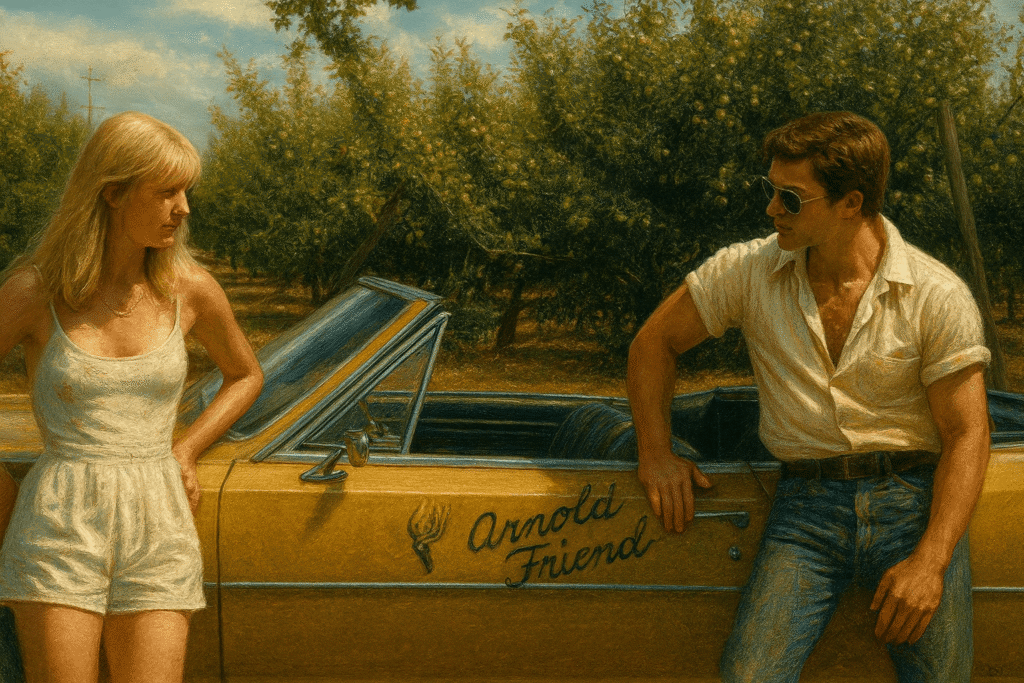

Seeing the story as a cautionary tale is both inaccurate and incomplete. It is inaccurate because cautionary tales typically follow a clear “bad choice → punishment → lesson” structure. Oates’ story never identifies a single decisive “bad choice” that causes Connie’s fate. Her behavior—flirting with boys, going to the drive-in, listening to music—remains within the ordinary boundaries of teenage experimentation. None of these actions directly summon Arnold Friend. He arrives with his own rehearsed plan, armed with a gold convertible, pop songs, and personal information he should not reasonably possess. He pretends to be a teenager to gain Connie’s trust, then escalates to explicit threats. The danger comes from his premeditated predation, not from any morally outrageous act on Connie’s part.

The cautionary-tale reading is also incomplete because it neglects the deeper existential questions posed by the title: “Where are you going, where have you been?” These questions reach beyond the immediate threat on Connie’s doorstep. They name her struggle to orient herself in the world, to understand who she is and what she is moving toward. Reducing the story to a warning about superficiality or premature independence misses this central tension. What drives Connie is not simple recklessness but a profound longing for belonging, purpose, and direction—longings that become clearer when her desires are examined more closely.

What Is Connie Yearning For?

Connie’s desires appear scattered—attention from boys, escape from her family, admiration for her beauty—but they can be understood as layers of a deeper need to discover meaning in life. Her pursuit of boys at the drive-in shows a desire to be “seen” and “acknowledged.” Her mother’s constant criticism points to a frustrated need for respect and affection at home. The story’s final image—Connie walking toward “much land she did not recognize except to know that she was going to it” (Oates, 1966/2005, p. 388)—suggests that beneath these surface cravings is a more fundamental yearning: to know where she is headed and what kind of life is possible for her.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs helps clarify this progression (Maslow, 1943). At the most basic level, Connie flirts and fantasizes about sex and romance, touching on physiological needs and the desire for safety and comfort. She also longs for love and belonging: she wants to share secrets with other girls, to be admired by boys, and to gain her mother’s approval. Beyond that, she craves esteem—recognition, validation, and the sense that she matters. At the top of Maslow’s hierarchy lies self-actualization, the drive to realize one’s potential and to live meaningfully. Connie has no language for this highest need, but her longing for “somewhere else,” for a different and more intense life, hints at it. Her behaviour is not simply shallow; it is an immature, misdirected attempt to address an existential question.

Once Connie’s yearning is understood in this way, the story’s symbolic structure comes into focus. Her journey is not a straightforward moral narrative but an apocalyptic one, where the collapse of her illusions reveals the emptiness of the “religion” she has been practicing all along.

A Christian-Apocalyptic Lens

If Connie’s deepest desire is to answer the questions of the title, the story invites a Christian-apocalyptic lens that diverges from the usual path of Revelation-style teleology. Instead of leading to redemption or revelation, Connie’s personal apocalypse ends in paralysis and surrender. Oates uses Christian-coded language to show how Connie attempts to find meaning through pop culture, only to discover its catastrophic insufficiency.

Throughout the story, religious vocabulary is displaced onto ordinary, secular spaces. The shabby drive-in restaurant Connie frequents, despite being fly-infested, is described as a “sacred” place that offers the “haven and blessings” she seeks. The pop songs playing there, which make “everything so good” for her, are likened to “church music” and something she can “depend upon” (Knudsen, 1994). In Connie’s world, music, drive-ins, and romantic fantasies function as substitutes for religion. They organize her feelings, give her rituals, and promise a sense of belonging.

This religious coding intensifies with explicit biblical references. When Arnold Friend pulls up in his gold car and points out the numbers “33, 19, 17” on it, they echo Judges 19:17, where a stranger is asked, “Where are you going? Where did you come from?” The echo of the story’s title is unmistakable. Even Arnold’s name carries a hidden message: removing the “r”s from “Arnold Friend” yields “an old fiend,” hinting at a demonic or satanic figure. He is both dazzling and frightening, a counterfeit saviour whose gospel is seduction and control.

Arnold embodies the very pop culture Connie idolizes. He dresses fashionably, plays Bobby King on the radio, and speaks in the slang of the moment. At first, he seems to offer the freedom Connie associates with adulthood. But as his mask slips, his charm becomes menacing. The apocalyptic moment arrives when Connie realizes that the cultural world she has treated as sacred—its music, its fantasies of romance, its promises of escape—cannot protect her. Physically, she faces the threat of rape or death. Psychologically, she becomes so overwhelmed that her senses dull; she hears her own fear “like music at a far distance,” and her body feels detached from her. Spiritually, the framework that sustained her collapses. Her idols are revealed as hollow and predatory, and the “religion” she has built around them offers no salvation.

To fully understand this collapse, it is helpful to turn to the philosophical figures whose work Oates explicitly engages: Kierkegaard and Kafka.To fully understand this collapse, it is helpful to turn to the philosophical figures whose work Oates explicitly engages: Kierkegaard and Kafka.

Why Kierkegaard and Kafka Matter Here

Before applying their ideas to Connie, it is helpful to sketch who Kierkegaard and Kafka are and why they belong in this discussion.

Søren Kierkegaard, a nineteenth-century Danish philosopher and theologian, is often called the “father of existentialism.” Writing against both dry academic theology and shallow cultural Christianity, he argued that genuine faith is not a matter of outward conformity but of inward passion. For Kierkegaard, the most important truths about how to live cannot be proved like a theorem; they must be embraced through what he calls a Leap of Faith—a subjective commitment that goes beyond what reason alone can justify (Kierkegaard, 1985). He also describes different “stages” of life—the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious—and warns that remaining at the aesthetic stage, devoted only to pleasure, eventually leads to despair. Kierkegaard’s work therefore links questions of faith, identity, and choice: what one trusts and commits to shapes who one becomes.

Franz Kafka, writing in the early twentieth century, explores a different but related problem. His novels and stories—such as The Trial—show characters caught in obscure systems, endlessly waiting for answers that never arrive (Kafka, 1998). The world he depicts is one in which old religious certainties have faded, but no stable new ground has solidified in their place. Critics such as Kohl (2019) argue that Kafka’s characters live in a condition of being “too late for faith, but too early for creating [their] own ground”: they can no longer rely on traditional belief, yet they have not managed to build a secure alternative. In this vacuum, people cling to what Kafka calls “charming, tiring distractions”—small pleasures, routines, and obsessions that distract from the underlying void.

Oates shows her familiarity with this tradition in her essay “Kafka’s Paradise,” where she reflects on moments of “unexpected grace” and on characters who experience a kind of spiritual crisis without clear religious resolution (Oates, 1973). Bringing Kierkegaard and Kafka together, then, helps illuminate Connie’s situation: she is a teenager in a culture where inherited faith is weak, pop culture is strong, and the self is searching for something to trust.

Connie’s Crisis: Kierkegaard’s Leap and Kafka’s Distractions

Traces of Kierkegaard and Kafka clarify how Connie’s Christian-like faith in pop culture leads not to meaning but to existential breakdown. Oates herself describes a scene from the story as a moment of “unexpected grace” (Oates, 1973). Just before Arnold arrives, Connie sits alone at home, listening to music: she “sat in the glow of slow-pulsed joy that seemed to rise mysteriously out of the music itself and lay languidly about the airless little room.” This experience resembles Kierkegaard’s notion of an inward awakening—a glimpse of a truth that cannot be grasped by reason alone but must be embraced through a Leap of Faith. For a brief moment, Connie’s joy seems separate from boys’ gazes or her mother’s criticism. The feeling is private, almost spiritual, a hint of a more authentic self.

However, Connie’s leap is misplaced. Instead of directing her faith toward a transcendent source, she invests it in the worldly symbols surrounding her: pop songs, romantic fantasies, Arnold himself. Here Kafka’s diagnosis becomes crucial. Oates draws on Kafka’s insight that modern individuals are “too late for faith, but too early for creating [their] own ground” (Kohl, n.d.). Connie no longer inhabits the world of childhood belief or traditional religious structure—her family offers little spiritual guidance, and conventional morality barely registers with her. Yet she is not ready to build an autonomous foundation of meaning. Her sense of self is fragmented by external pressures: the boys who look at her, the mother who belittles her, the music that temporarily lifts her out of boredom.

In this Kafkaesque limbo, Connie turns to what is most available: the radio, daydreams, and the attention of boys. These are less deliberate choices than reflexive retreats into what Kafka calls “charming, tiring distractions.” They promise intensity and escape but ultimately prevent the sustained introspection required to form a stable identity. As long as these distractions function, they obscure the void underneath. Once they fail, the void is all that remains.

Connie’s final trance-like walk toward Arnold dramatizes this collapse. She is no longer able to act freely, to choose, or even to fully understand what is happening. She can only “watch herself” go to him, as if her agency has been hollowed out. Her surrender is not a courageous sacrifice nor a moment of revelatory faith; it is the result of spiritual exhaustion. The more she has tried to construct meaning through surface-level desires and pop-cultural rituals, the further she has drifted from any enduring ground. Oates describes this kind of breakdown as a “suicidal struggle against the self,” where the self becomes both the battleground and the casualty.

The “land she did not recognize” at the end does not promise a new, meaningful beginning. Instead, it stands for the loss of orientation itself: a space where faith, identity, and purpose have dissolved. Suspended between Kierkegaard’s leap toward authentic faith and Kafka’s world of endless distraction, Connie belongs fully to neither. Her crisis remains unresolved.

Conclusion

“Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” resists the neat structure of a cautionary tale. Rather than punishing a girl for superficiality or premature independence, it explores the deeper existential confusion at the heart of modern adolescence. Through a Christian-apocalyptic lens shaped by Kierkegaard and Kafka, Oates shows a young girl searching for meaning in a world where neither inherited faith nor popular culture offers stable ground. Arnold Friend is not a simple agent of moral retribution but the embodiment of a false religion that promises belonging and purpose and delivers only terror and emptiness.

Connie’s final submission to Arnold is not a moral lesson but an image of spiritual paralysis: a point where the desire for purpose collides with the collapse of all meaningful frameworks. In this light, the title’s questions—“Where are you going, where have you been?”—do not guide Connie toward clarity. They expose that, for her and perhaps for many in her generation, direction itself has already been lost. The story leaves us not with an answer but with the unsettling possibility that some questions about meaning and belonging cannot be resolved within the limited “religions” of pop culture and social validation.

References

Cougill, J. N. (2019). Vice and virtue: Joyce Carol Oates’s collection Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? Stories of Young America as a morality manual for adolescents [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Southeast Missouri State University.

Kafka, F. (1998). The trial (B. Mitchell, Trans.). Schocken Books. (Original work published 1925)

Kierkegaard, S. (1985). Fear and trembling (A. Hannay, Trans.). Penguin Books. (Original work published 1843)

Knudsen, J. (1994). [Review of the short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”, by J.C. Oates]. World Literature Today, 68(2), 369–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/40150226

Kohl, M. (2019). Kafka on the loss of purpose and the illusion of freedom. The Polish Journal of Aesthetics, 53(2), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.19205/53.19.4

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Oates, J. C. (1973). Kafka’s paradise. The Hudson Review, 26(4), 623–646.

Oates, J. C. (2005). Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? In R. S. Gwynn (Ed.), Fiction: A pocket anthology (4th ed., pp. 373–388). Pearson Longman. (Original work published 1966).