Sivakumar Abhayaa, November 2025

Introduction

When The Lego Movie (Lord & Miller, 2014) first appeared in cinemas, it was quickly recognised as a colourful children’s film, with critics even noting its function as an advertisement for Lego itself (Walters, 2014; Barnes, 2014). Set in a universe built entirely of Lego bricks and populated by anthropomorphic minifigures, known as MiniFigs, the film follows Emmet Brickowski, a cheerful construction worker who lives in the perfectly ordered Lego city of Bricksburg, where every citizen wakes, works, and plays according to “the instructions” (a step-by-step visual guide on how to build things, similar to the instruction manuals one gets along with Lego sets) Emmet hums along to the infectious tune “Everything is Awesome,” content to obey and belong. When the tyrannical Lord Business threatens to freeze the Lego universe with a superglue-like weapon called the Kragle, Emmet accidentally discovers the “Piece of Resistance,” the cap that can stop it. Mistaken for the prophesied hero known as “the Special,” he joins a band of rebels led by the blind sage Vitruvius to restore creativity to the Lego realm. On this surface level, The Lego Movie embodies all the hallmarks of a family film with vivid CGI animation, fast-paced humour, and a message about teamwork and believing in oneself.

However, beneath its colourful exterior lies a deeper narrative that feels out of place in a children’s film. What begins as a story about defeating a villain expands into a meditation on revelation, prophecy, and sacrifice. The film transforms the familiar structure of a hero’s journey into a theological allegory about creativity and control. Vitruvius’s prophecy and Emmet’s eventual self-sacrifice echo biblical narratives of divine mission and redemption, while Lord Business’s obsession with order recalls the wrathful lawgiver of the Old Testament. These religious and apocalyptic elements are not incidental. They form the film’s symbolic foundation. In using biblical imagery, The Lego Movie stages a battle between oppressive rigidity and liberating creativity. It does so through a language of prophecy, judgement, and revelation that transforms a simple story about toys into a reflection on the tension between rigid order and unrestricted imagination. Thus, this article argues that The Lego Movie is, at its core, an apocalyptic text that uses biblical allegory to dramatise this struggle, transforming a simple children’s film into a reflection on revelation and renewal.

Why Apocalyptic Religious Allegory in a Children’s Film?

Firstly, one might wonder why would a children’s movie, designed to sell toys, lean so heavily on religious allegory and apocalyptic tropes? The answer lies in how the film transforms theological ideas into a language that children can intuitively understand. The Lego Movie borrows the grammar of biblical apocalypse, such as prophecy, sacrifice, revelation, not to preach doctrine, but to dramatise universal experiences of creation, control, and renewal. For a story set in a world made of toys, these motifs translate complex theological concepts into acts of play. The prophet becomes the voice of imagination, the messiah becomes the believer in creativity, and the lawgiver becomes the embodiment of order. In this way, the film turns theology into narrative structure, presenting cosmic conflict in a form accessible to young audiences. By embedding apocalyptic imagery within a tale of collaboration and invention, The Lego Movie suggests that revelation and salvation are not divine events beyond human reach, but creative acts that emerge from ordinary imagination itself.

Characterisation as Theological Allegory

The religious undertone of the film is most visible through its reworking of biblical archetypes. Emmet, Vitruvius, and Lord Business correspond to the Christ-like saviour, the prophetic herald, and the lawgiving deity. Together, they shape both biblical cosmology and the film’s moral world. In the Bible, these roles sustain the apocalyptic narrative. The prophet announces revelation, the messiah fulfills it, and the lawgiver enforces divine order. In The Lego Movie, these archetypes are reimagined to explore the tension between imagination and authority. Through them, the film makes theological concepts such as prophecy and salvation more digestible by casting them in the playful language.

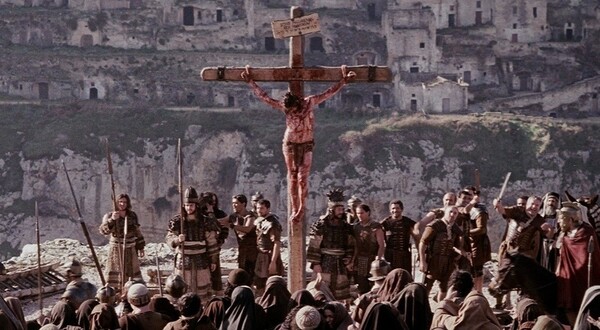

At the centre of this apocalyptic narrative is Emmet, whose arc closely resembles the biblical Christ. Initially dismissed by his peers as unremarkable, Emmet is the “stone the builders rejected” (NRSVUE, 2021, Psalm 118:22), a figure of ordinariness and insignificance. His lack of creativity mirrors Christ’s humble beginnings as a carpenter’s son, someone seemingly unsuited to messianic destiny (Kozlovic, 2004). Emmet’s journey follows a recognisably Christ-like trajectory. He is misunderstood, mocked, and disbelieved by those around him, echoing how Jesus was rejected three times. As much as he tries, he is not able to rid himself of the “Piece of Resistance” which is stuck to him, mirroring how Christ was the prophesied messiah, destined and preordained from the beginning to fulfil his role as the chosen one. He ultimately chooses self-sacrifice, throwing himself into the abyss to stop Lord Business’s plan. In this act of apparent death, Emmet parallels Christ’s crucifixion. Like Christ, however, his death is not the end. Through faith and belief (literally his belief in his own capacity to create) he returns, resurrected, to inspire others (Johnston, 2007).

Emmet’s self-sacrifice visually parallels traditional Christian imagery of crucifixion of Christ, suggesting that his sacrifice is meant to mirror the redemptive role of a saviour figure.

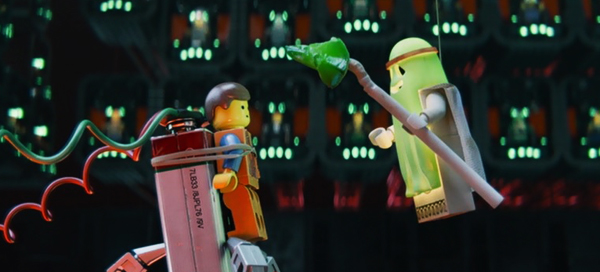

If Emmet embodies the messiah, then Vitruvius represents the prophet who announces revelation and guides others toward it. In biblical tradition, prophets act as intermediaries between divine truth and human understanding, revealing what others cannot see. Vitruvius fulfils this role through his spiritual awareness, for although he is blind, he perceives the importance of creativity that the citizens of Bricksburg overlook. His blindness becomes a metaphor for inner sight, a biblical motif where physical limitation signifies divine insight. As the one who proclaims the coming of “the Special,” he performs the prophetic duty of announcing salvation before it takes place. When he dies and later reappears as a spirit, he continues to affirm faith even in the absence of proof. His soul accompanies Emmet throughout his journey, acting a guide and mentor even beyond his death. This references the Transfiguration in Matthew 17:1–8 (NRSVUE, 2021), where prophets Elijah and Moses reappear from the afterlife to strengthen him before his sacrificial journey. Their presence provides divine endorsement and reassurance at a pivotal moment. Similarly, Vitruvius reappears to Emmet in luminous, elevated form precisely when Emmet is uncertain of his purpose. His ethereal presence reassures Emmet of his calling, confirms the truth of the prophecy, and strengthens him for the self-sacrifice he is about to undertake. In both scenes, a dead or divine figure returns temporarily from beyond to reveal truth, restore confidence, and prepare the chosen figure for a redemptive act. Vitruvius’s later confession that he invented the prophecy seemingly challenges his authority. Yet rather than undermining his role, it reveals the rhetorical power of prophecy. Prophecy, even when fabricated, can still act as rhetorical tools to inspire belief (Stockmann & Graf, 2020; Mazzarella & Hains, 2019). Vitruvius’s lie becomes faith’s catalyst, showing that prophecy’s truth may lie in its capacity to inspire, rather than in its literal accuracy. Through this device, Vitruvius comes to embody the inspirational role of a prophet.

Like traditional depictions of Christ’s baptism, Vitruvius’s appearance functions as a moment of revelation, affirming Emmet’s worth and calling, blessing him with the confidence to rise as the Special.

The prophetic figures surrounding Christ mirror Vitruvius’s role as the film’s guiding spirit, offering vision, meaning, and insight from beyond and guiding Emmet toward understanding his purpose.

If Emmet represents Christ and Vitruvius the prophet, then Lord Business functions as a parody of the wrathful God of legalism. His obsession with order and desire to fix every brick in place with the Kragle arises not from pure malice but from fear. He believes perfection and order can only be achieved through total immobility. In this sense, he mirrors the Old Testament deity of commandment and punishment, where disobedience threatens the entire cosmic order. Lord Business’s catchphrase, “I will decide what goes where,” echoes the authoritarianism of systems that insist on one truth, one law, one vision of order. As Goggin (2017) observes, the film parodies what she calls a neoliberal ‘security culture’, where people trade freedom for the illusion of safety. Lord Business can be seen not simply as a villain, but as a symbolic figure of authoritarian control whose insistence on rigid order becomes a theological as well as political obstacle to creativity. By casting him as both deity and dictator, the film highlights how religious orders can slide into authoritarianism, where sacred law transforms into restrictive dogma (Bendle, 2005).

Together, these figures represent a theological force in tension with each role depending on the others. Emmet’s salvation narrative only unfolds through Vitruvius’s prophecy and culminates in Lord Business’s act of judgement. In a sense, the film constructs its own miniature cosmology and theology, reworking traditional biblical archetypes to form a larger narrative that uses a familiar grammar of religious archetypes to tell a story about creativity and imagination.

Paradise, Fall, and Collective Salvation

The film’s apocalyptic imagination goes beyond its characterisation into its settings and storyline.It does so by mirroring the broad structure of Christian eschatology—moving from an Edenic creation, to a catastrophic fall, and finally toward a vision of collective salvation—which extends the allegory beyond individual characters into the very architecture of the film’s world.

Cloud Cuckoo Land, ruled by the exuberant unicorn-cat Unikitty, serves as the film’s Edenic space. It is a realm of unrestrained colour, noise, and imagination. Here the Master Builders, an underground group of creators who can assemble anything from memory without instructions, thrive in unbounded freedom. The scene where Unikitty explains that “There are no rules! There’s no government, no bedtime, no consistency!” echoes Genesis 2:25 (NRSVUE, 2021) where Adam and Eve are depicted as the purest form of innocence with no rules and limitations. Yet Cloud Cuckoo Land is not sustainable. It is literally destroyed by Lord Business’s forces, its colourful chaos obliterated in fire and destruction. A paradise without order collapses as easily as a world enslaved by rules. Scholars of apocalyptic literature observe that visions of paradise often are paired with scenes of judgment and renewal. As McGinn (1998, pp. 78–79) observes, the Book of Revelation’s New Kingdom only arises after the collapse of Eden. The annihilation of this paradise underscores the biblical plot of the loss of innocence and expulsion from Eden as seen in Genesis. The film thus establishes its core message that creation requires both structure and imagination. This then prepares the ground for revelation.

Like the biblical expulsion from Eden, the fall of Cloud Cuckoo Land illustrates the loss of unbounded innocence and the fragility of a paradise without limits.

The apocalypse is not only about annihilation but also about revelation. As Keller (1996) reminds, the Greek root of apocalypse, “apokalypsis”, means “unveiling” or “disclosure”. In other words, a revelation of truth that changes how people see the world. In The Lego Movie, this moment comes when Emmet learns that the Lego universe is nested within the “real” world of a boy (Finn) and his domineering father (the “Man Upstairs”). The revelation that there is something larger than this world very clearly echoes John’s vision in the Book of Revelation, when the veil is lifted to reveal a cosmic realm behind the earthly plane, a dimension where divine forces battle to prepare for the coming of the New Kingdom. In both, the apocalypse is visualised not as destruction but as the revelation of another order waiting to materialise.

The prophetic vision given to John in Revelation parallels Emmet’s revelation of the real world, highlighting apocalypse as an act of seeing what lies beyond the visible plane.

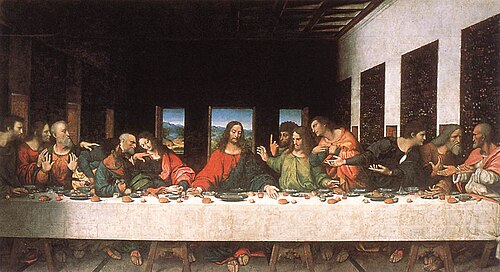

From this revelation comes the film’s final theological gesture: collective salvation. Emmet’s journey is not about securing his own messianic status but about unveiling a truth that extends it to everyone. That truth is that “the Special” is everyone. The only caveat is that they just have to believe in it themselves. In theological terms, this mirrors the belief that Christ’s redemptive act is for everyone (NRSVUE, 2021, Galatians 3:28) and faith alone is sufficient for salvation (NRSVUE, 2021, Galatians 2:16). As Marsh (2004, p. 112) notes, cinema often democratises grace by extending it beyond institutions and hierarchies. The film visualises this through the collective rebuilding of the Lego world where every citizen contributes to renewal. Ordinary figures who once always followed “the instructions” begin to invent freely, combining mismatched pieces and working side by side to restore their world. Even Lord Business lays down his weapons and participates in creation. This sequence mirrors the reconciliation in the real world, where Finn and his father build together for the first time. Kozlovic’s (2004) notion of the “pluralisation of messiahship” captures this transformation where everyone becomes the Christ-figure and takes part in renewal and rebuilding, turning spectators into co-redeemers. This again mirrors biblical teachings on how the “body of Christ” belongs to everyone (NRSVUE, 2021, 1 Corinthians 12:12).

The Last Supper evokes the idea of communal participation in a transformative act, mirroring how the film turns creation and renewal into a shared responsibility embraced by all, where ordinary figures participate together in creation and transformation.

This progression also provides a crucial supporting reason for why The Lego Movie is an appropriate site for apocalyptic religious allegory: it does not merely rely on character parallels, but structurally reproduces the broad sweep of Christian eschatology. The movement from Cloud Cuckoo Land as an Edenic paradise, through its destruction as a fall from innocence, and finally toward the film’s vision of collective rebuilding and renewal, mirrors the biblical narrative arc that moves from creation to fall to redemption. By aligning its settings and story beats with this theological sequence, the film completes its allegory, with the notions of creation, destruction, revelation and renewal transforming a simple children’s movie into a weighty metaphor for biblical apocalypticism.

Conclusion

The Lego Movie reimagines the apocalypse as revelation rather than destruction. Through Emmet’s messianic awakening, Vitruvius’s prophetic guidance, and Lord Business’s conversion from order to grace, the film transforms theology into play and renewal. It shows how even a children’s story can carry profound spiritual meaning, turning the end of worlds into a hopeful language of imagination, collaboration, and creation. More broadly, it reflects a growing tendency in children’s media to frame apocalyptic themes as lessons in empathy and creative resilience.

References

Barnes, H. (2014, December 12). The Lego Movie writer/directors: “We wanted to make an anti-totalitarian movie for kids.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/dec/12/lego-movie-writers-phil-lord-christopher-miller-interivew

Bendle, M. F. (2005). The apocalyptic imagination and popular culture. The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, 11(1), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.3138/jrpc.11.1.001

Canavan, G. (2017). Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot: Apocalypse as children’s entertainment. Science Fiction Film & Television, 10(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.3828/sfftv.2017.4

Goggin, J. (2017). “Everything is awesome”: The Lego movie and the affective politics of security. Finance and Society, 3(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v3i2.2574

Johnston, R. K. (2007). Reel spirituality: Theology and film in dialogue. Baker Academic.

Keller, C. (1996). Apocalypse now and then: A feminist guide to the end of the world. Beacon Press.

Kozlovic, A. K. (2004). The structural characteristics of the cinematic Christ-figure. The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, 8(1), 5–5. https://doi.org/10.3138/jrpc.8.1.005

Lord, P, & Miller, C. (Directors). (2014). The Lego Movie [Film]. Warner Bros.; Village Roadshow Pictures; RatPac-Dune Entertainment.

Marsh, C. (2004). Cinema and sentiment: Film’s challenge to theology. Paternoster Press.

Mazzarella, S. R., & Hains, R. C. (2019). “Let there be Lego!”: An introduction to cultural studies of Lego. In S. R. Mazzarella & R. C. Hains(Eds.), Cultural studies of Lego (pp. 1–20). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32664-7_1

McGinn, B. (1998). Visions of the end: Apocalyptic traditions in the Middle Ages. Columbia University Press.

New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition (NRSVUE) Bible . (2021). https://www.biblegateway.com/versions/New-Revised-Standard-Version-Updated-Edition-NRSVue-Bible/

Stockmann, N., & Graf, A. (2020). “Polluting our kids’ imagination?” Exploring the power of Lego in the discourse on sustainable mobility. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 231–246. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15487733.2020.1802142

Walters, B. (2014, February 11). The Lego Movie – a toy story every adult needs to see. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/feb/11/lego-film-subversive-countercultural?

Wloszczyna, S. (2014, February 7). The Lego Movie Movie Review & Film Summary (2014). Roger Ebert. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-lego-movie-2014