By Yu Jia Lin

Note of clarification: The title, Nausicaä of The Valley of The Wind, will be referred to as Nausicaä (italicized). The character will be referred to as Nausicaä (non-italicized).

Films produced by Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki have mostly focused on social and environmental issues. In particular, Nausicaä of The Valley of The Wind (1984)[1], one of their oldest films, is well-known for its strong environmentalist theme, especially given its year of production that coincided with Japan’s pursuit of post-war economic growth and the ensuing environmental problems. To attain maximum economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s, Japan incorporated Western technology that focused on shaping nature according to human needs.[2] The onset of many environmental problems led to a drastic change towards a pro-environmentalist stance and by the 1970s, Japan implemented environmental protection laws.

The implementation of Western technology in Japan can be viewed as a metaphor for the importation of Western cultural values towards the environment at that time. With the function of Western technology being the domination of nature for human desires, by extension, this reflects how the West views the environment as well. As stated in The Ethics of Japan’s Global Environmental Policy, by Midori Kagawa-Fox, the West is associated with dominating nature, where a clear divide exists between nature and man. Kagawa-Fox compares this against Japan’s environmental ethics, which include “empathy towards nature” and a “strong relationship” between people and nature based off Nihonjinron[3] and Shintoism. Respect, admiration and living in harmony with nature are values the Japanese people treat nature with. However, Kagawa-Fox qualifies these unique characteristics of Japan: she posits that Japan’s environmental policy, in actuality, does not lie truly with the environment, but with the economy.[4]

… there is a strong relationship between the Japanese and their environment, and that this empathy with nature forms a significant part of Japanese cultural values.

Midori Kagawa-Fox, The Ethics of Japan’s Global Environmental Policy

This therefore serves as a contextualization for Nausicaä, with its post-apocalyptic setting of the earth suffering from the harmful effects of industrialization, and the over-exploitation of nature’s resources. The film portrays a continuous tension between two characters in particular, Nausicaä and Kushana, the princess-generals of their countries, The Valley of The Wind and Tolmekia respectively. The two characters oppose each other diametrically in how they perceive the environment.

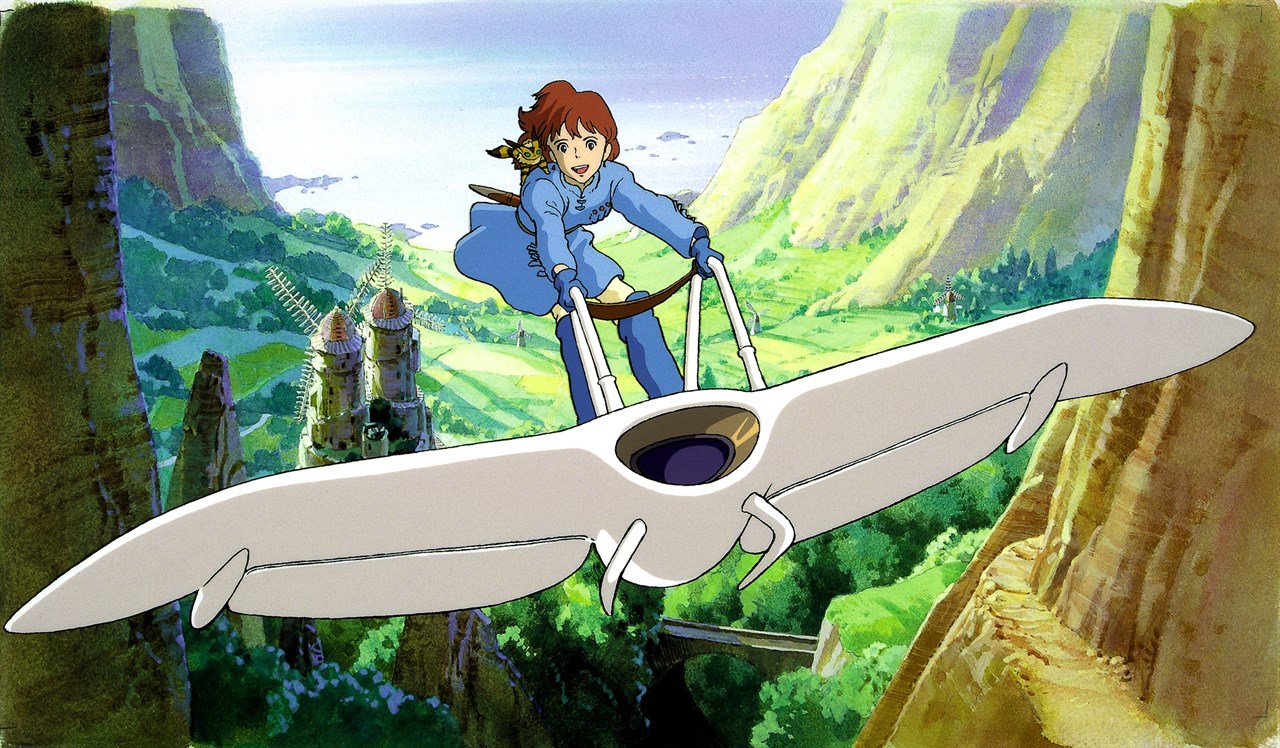

Nausicaä is portrayed as a protector and lover of nature and bears the special ability to communicate with it. Conversely, Kushana desires to reinstate the dominance of man through the destruction of The Sea of Decay – a toxic and poisonous forest that arose out of the period of industrialization and is a threat to mankind, which is founded upon a personal hatred from a disfigurement by an Ohm.[5]

How are the two characters representative of ideological differences between Japan and the West? Furthermore, while the film ends in obvious support for Nausicaa, the environmentalist, a deeper look into the ending reveals a sense of ambiguity. To what extent does the film support the reputation that Japan has built for itself in the global environmental landscape and the assumptions of Japan’s environmental stewardship?

By referencing Kagawa-Fox’s analysis of the differences between Japan and the West’s environmental ethics, this article hence argues that Nausicaä and Kushana respectively represent the ideological differences between Japan and the West. Additionally, I further argue that the film depicts the unique cultural position of Japan environmentally: while it is fundamentally different from the West, this is made ambiguous through its actions that speak otherwise.

Princess to Subjects: The Relationship between characters

Nausicaä is a film that illustrates a tight interweaving of man and nature within the same social space, with the interactions between man and nature under constant scrutiny. This can be extrapolated from the interactions within humanity itself – namely between the princesses and their subjects. The German philosopher, Martin Heidegger, in The Question concerning Technology, posits that nature is “enframed” as a “standing reserve” in an exploitative sense, to the point where humans themselves are “enframed” as part of it, and hence can be exploited too.[6] Our perceptions of nature are therefore an extension of how we perceive fellow humans, given how they are inextricably linked in the same space. Therefore, the initial contrast between how Nausicaä and Kushana treat their subjects is a useful lens into the examination of their respective relationships with nature. Two extremely different relationships are seen throughout the film between Kushana and her own army; and Nausicaä and her people.

Undeniably, both leaders treat their subjects with great love and care. However, they position themselves differently. While Kushana is an authoritative leader, Nausicaä is instead an approachable figure of authority. Kushana’s domination of her army is conveyed through the literal and metaphorical elevation of her position above all. This is set out for us right at the beginning – in the scene where Tolmekia invades The Valley, her Counselor, Kurotowa, stands one level below her announcing her status, while all other unnamed, unfaced soldiers are on ground level. The hierarchy within the army is reinforced further when viewers understand how her word is final throughout the film.

Even though Kushana commands the respect of the army through her status, it is notable that this respect is revealed to be performative and customary. The reaction of Kurotowa to Kushana’s potential death when he hears of the explosion of the ship she was flying in is shockingly cynical – instead of the expected mourning, he grins slyly towards the growing “Great Warrior”,[7] stating “Either fortune’s finally smiling on this lowly soldier, or it’s a trap set to destroy me.” This self-interested response hence reveals a superficial relationship between the unwelcoming Kushana and her subjects.

Viewers are given the exact opposite between Nausicaä and her people. While her subjects treat her respectfully through the formal address of her title, “Hime-sama”,[8] Nausicaä is consistently portrayed amongst her citizens without the tensions of a hierarchy. The entire community is supportive and bonded, with respect for the leaders borne out of true admiration for them. Nausicaä’s friendly and approachable character effects a relationship of mutual trust and protection. A touching scene between Nausicaä and her people before she leaves with Tolmekia as a hostage portrays a collective mourning at her departure, made poignant through the emotional cries of three young children who present a farewell gift of Chiko nuts.[9] The deep connection and attachment her people hold for Nausicaä contrasts jarringly against the detached, self-serving scenario we see in Tolmekia.

Princess to nature: The relationship they share with nature

Given the proximity of humans and nature in the society of the film, the film uses the relationship both leaders share with their subjects to mirror the relationship they share with nature. The imposing role taken by Kushana over her subjects is similar to how she treats nature. Perceiving it as an entity to be ruled, viewers are made aware of this through her declaration of war against The Sea of Decay: “We shall burn away the Sea of Decay and resurrect the Earth!… We have revived the miraculous skills and powers that once allowed humans to rule the Earth.” Kagawa-Fox quotes Richard Evanoff in his analysis of Western environmental ethics: “Western society emphasizes … (the) ‘domination’ of nature”. Just as Kushana dominates her army, she treats nature through the Western notion of ‘divide and conquer’.[10] The resolve she has towards reinstating the domination of man over the earth is depicted in a scene where she is held captive by The Valley – “Burn the Sea of Decay, kill the insects, and restore the human world”, the imperative repeated with a burning intensity.

To Kushana, the only solution is to remove the threat nature poses and assert domination, harming nature in the process of doing so. Her adamant refusal to understand how humans can cooperate with nature is driven by how she singularly focuses on a past injury that nature inflicted upon her, which fuels her personal hatred. Her inability to reconcile the presence of nature and man within the same space evinces Kagawa-Fox’s own perspective of Western environmental ethics that bear a “clear division between humans and non-humans”.[11] Ultimately, nature, in Kushana’s eyes, threatens man’s survival, to be annihilated and dominated by man.

Togetherness is the key in shaping environmental ethics in Japan, whereas in the West there is a clear division between humans and non-humans. Moreover, while in the West environmental ethics is a one-way approach, in Japan it is two-way, involving gratitude and care.

Midori Kagawa-Fox, The Ethics of Japan’s Global Environmental Policy

Nausicaä, the environmentalist heroine, arguably treats nature similarly to her people, perhaps with even greater significance. The deep love she has for her people motivates her to take herself hostage to Tolmekia, and this parallels the extent of her love for nature that eventually culminates into self-sacrifice. Nausicaä’s relationship with nature is clearly explained by Kagawa-Fox, who states how “the traditional Japanese approach to the ecosystem has been one of harmony, reciprocity, care and respect”.[12] Rather than the extreme hostility seen in Kushana, Nausicaä sees nature through a cooperative lens: her discovery of a discarded Ohm shell is filled with pleasure and admiration over how it can be used to make tools for the village. Rather than threatening human survival, it is instead a resource rich entity aiding human sustenance.

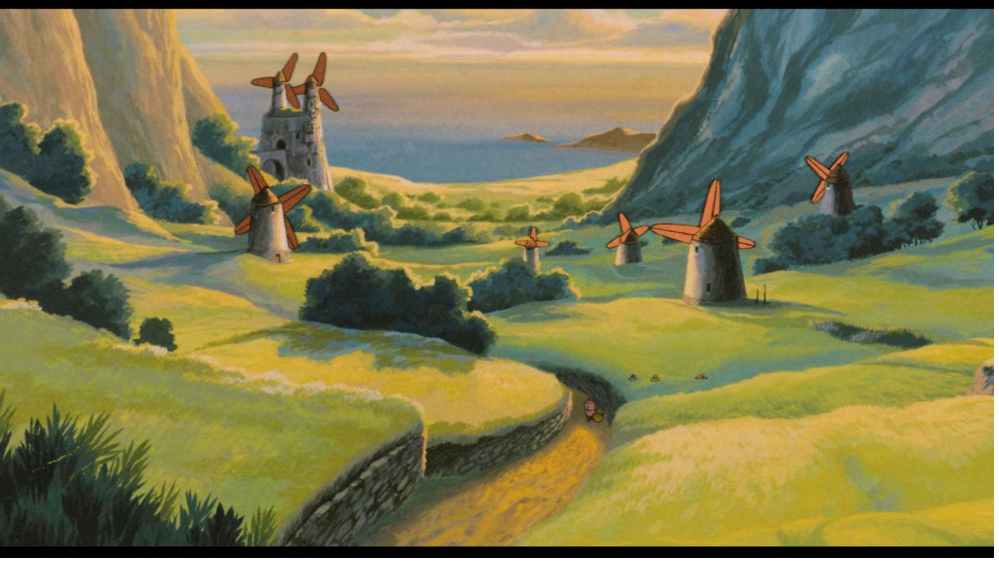

Furthermore, unlike Kushana, Nausicaä does not exploit and destroy nature to achieve her goals; she instead cares for it even as she utilizes nature for sustenance. This is most aptly shown through the uncorrupted, green landscapes of The Valley, an abnormality that exists in the film precisely because of how the daily activities of the people do not pollute nature.

Nausicaä also treats nature protectively. The Valley lives on the edges of The Sea of Decay and its citizens are eventually paralyzed by the poisons due to the close proximity –– one of them being Nausicaä’s own father, whom she deeply loves. The inevitability of this “fate” is met with sadness and resignment from Nausicaä. Similar to Kushana, she too has been harmed by Nature, through the loss of her father’s mobility. Yet interestingly, viewers do not see the same hatred –– Nausicaä stands on the other extreme. The deep love she has for nature motivates the self-sacrificial attempt she takes to prevent the rage of the Ohms. Even as she knows full well that her attempt may fail and that her death is guaranteed upon failure, she goes forth with determination, leading to her eventual death. Evidently, nature holds a wholly different position for Nausicaä, in line with Japan’s environmental ethics of harmony and empathy.

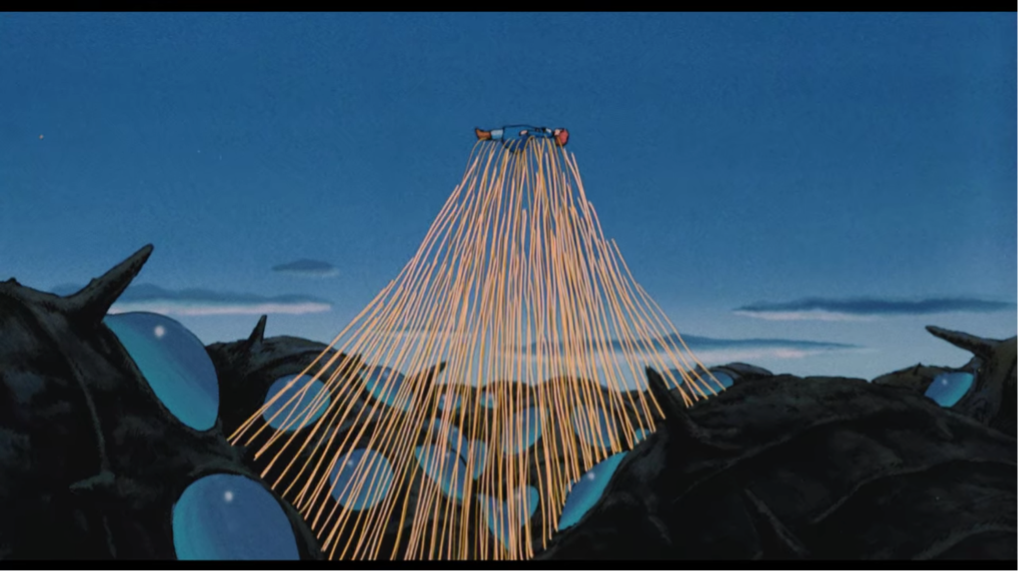

The film portrays an ending that visibly supports Nausicaä, and hence Japan. Her death is overturned, and Nausicaä is revived by the Ohms in a dramatic, miracle-like scene where golden ‘light’ disperses down upon the rest of the characters as the Ohms heal Nausicaä through golden tendrils. As said by Obaba,[13] the scene displayed “such friendship and sympathy” – a scene of reciprocation as they have recognized the sacrifice and goodwill of Nausicaa. The ending is hopeful, optimistic, and above all, presents a future where man and nature harmoniously coexist.

An Ambiguous Ending

Despite the positive ending that leans heavily in support of Nausicaä and Japan, the ending remains ambiguous, spotting hints of Western ideology remaining present in Japan. Kushana is still decked in full armour and leaves The Valley in Tolmekian battleships, the same way she invaded it.

The continued unquestioned presence of Kushana in Nausicaä’s world can be interpreted as an indication of how Western values remain present even after Japan changed its stance. This is affirmed by how Kagawa-Fox describes Japan: harmonious living with nature is “not reflected in its overseas practices; a rapacious appetite for natural commodities, such as fish and timber, has tarnished the country’s reputation.”[14] The presence of the Western values of dominating nature and exploiting it for human desires, remain unquestioned in Japan, just as Kushana remains as an unseen presence within the community.

Japan’s traditional image of living close to, and in harmony with, nature is not reflected in its overseas practices; a rapacious appetite for natural commodities, such as fish and timber, has tarnished the country’s reputation.

Midori Kagawa-Fox, The Ethics of Japan’s Global Environmental Policy

In conclusion, this essay responds to the divide between Western and Japanese environmental ethics that is portrayed through Kushana and Nausicaä. The relevance of the film, even as it turns 37 years old this year, explains its continued success till today. Ultimately, it provokes further questions related to the present position Japan holds as a global leader in sustainability. To what extent does Japan truly hold this position? How strongly is Japan influenced by the West with regard to the environment?

References

[1] Nausicaä of The Valley of The Wind, directed by Hayao Miyazaki (1984; Japan: Netflix, 2020).

[2] Yasuhiro Murota, ‘Culture and the Environment in Japan’, Environmental Management 9, No. 2 (1985): 105-111, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01867110

[3] Nihonjinron refers to the study of Japanese characteristics.

[4] Midori Kagawa-Fox, The Ethics of Japan’s Global Environmental Policy: The conflict between principles and practice (New York: Routledge, 2012), 26, 32

[5] Ohm refers to a massively huge and powerful insect that is all consuming when blinded with rage. At its worst, it has consumed individual countries, wiping out civilization by the masses.

[6] ‘Gestell’, Wikipedia, 5 April, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestell

[7] A revived weapon from the pre-apocalyptic age that Tolmekia wishes to weaponize and destroy The Sea of Decay.

[8] ‘Princess’ in formal Japanese.

[9] Chiko nuts are nuts that are special to The Valley, said to be good for health and strength. This scene shows the young children giving many Chiko nuts to Nausicaä, which can be inferred to have taken much time and effort to harvest. The farewell gift is a gift of well-wishes that embodies the love her people have for Nausicaä.

[10] Cited in Kagawa-Fox, 26

[11] Kagawa-Fox, 32

[12] Kagawa-Fox, 36

[13] A respected elder with prophetic sight from The Valley.

[14] Kagawa-Fox, 8