By Wong Zhi Wei

Introduction

In Japanese society, apocalyptic media often reflects the defining spirit of a particular time period. M. Tanaka in Apocalypticism in Postwar Japanese Fiction (2011) denotes three time periods in modern fiction that define apocalypticism in post-war Japanese media. These are: “the idealistic age” (risō no jidai), from 1945 to 1970; “the fictional age” (kyokō no jidai), from 1970 to 1995; and “the age of impossibility” (fukanōsei no jidai), from 1995 to the present day[1]. The first age is characterised by works being produced as a response to Japan’s defeat in World War II, portraying the apocalypse as an “overtly foreign” threat to reality, and is often referenced as the classical apocalypse in popular culture. I will be using both terms interchangeably. Secondly, the fictional age in contrast frames the apocalypse in fictional worlds. Engendered by unprecedented growth and change to society, people sought to find ideals in post-apocalyptic worlds. Finally, the apocalyptic age of today is characterised by weakening interpersonal relationships, leading people to retreat from society, having lost faith in Japan’s pre-existing social and political order.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is an anime television series that aired from 1995-1996. It aired during what is commonly known as Japan’s “lost decade” from 1990-2000. Interestingly, Evangelion possesses characteristics from all three time periods – powerful aliens seeking to destroy humanity emblematic of the classical apocalypse, a fictional post-apocalyptic world reflective of the fictional age, and a narrative that highlights the hardships of human connection. Therefore, how can we understand and reconcile Evangelion’s apparent ‘apocalyptic hybridisation’? In this article, I seek to explore Evangelion’s interpretation of the apocalypse through analysing its pluralistic apocalyptic imagery and its representation of the Hikikomori – a defining aspect of the lost decade. I will rely on Tanaka’s periodization of Japanese apocalypticism and will be focusing on the idealistic age and the age of impossibility as these two are most prominent in Evangelion’s apocalyptic language. Napier has already compared works between the idealistic and fictional age, wherein she denotes developments in narrative structure from a more conventional “secure horror” in Godzilla (1954) to “a postmodern privileging of narrative movements and lack of closure” in Akira (1988)[2]. Nevertheless, she recognises that Japanese science fiction, like Evangelion, “emphasises the darker side of modern Japanese society” and tends to reveal “the imagination of disaster[3]. Hence, these works set the precedent for further exploration of Japanese apocalypticism in this article.

I argue that Evangelion possesses characteristics from different time periods of apocalyptic fiction because it seeks to subvert the classical apocalyptic genre through its divergent imaginations of the end of the world. It does so by illustrating differing apocalyptic languages – religious portrayals of the apocalypse indignant of foreign invaders contrasted with an allegorical critique of social withdrawal reflecting the plight of the Hikikomori. By initially presenting only the threat of the classical apocalypse, Evangelion subverts the viewer’s expectations about what constitutes the threat to humanity when the classical apocalypse is rendered moot and a new threat to humanity arises. Therefore, Evangelion does not only convey the anxieties of Japan at the time it was produced, but also contrasts it with past anxieties, thus possessing apocalyptic hybridisation. Finally, its representation of the Hikikomori through the portrayal of its main character, Shinji Ikari, serves to capture the zeitgeist of the lost decade by illustrating societal anxiety in young adults failing to cement their role in society.

A New Genesis

Produced by Studio Gainax and directed by Hideaki Anno, Neon Genesis Evangelion (originally Shinseiki Evangerion) aired from October 1995 to March 1996[4]. In 1997, The End of Evangelion was released, serving as an anime feature film that sought to build on as well as reimagine the ending of the television series. Set fifteen years after a worldwide cataclysmic event, Evangelion takes place in the futuristic city of Tokyo-3. The show follows protagonist Shinji Ikari who, at the summoning of his father, ends up piloting a biomechanical robot known as an Evangelion. His mission is to fight and destroy Angels, antagonistic extra-terrestrial beings sent to destroy Earth. Over the course of the show, he is introduced to fellow “Eva” pilots Rei Ayanami and Asuka Langley. Together, they attempt to stop the Angel apocalypse.

For two thirds of the series, Evangelion follows a straightforward episodic plot, where each episode comprises of a different Angel invading Earth and the pilots stopping them. However, from episode 16 onwards, the show begins to shift towards an introspective look at the characters, starting with Shinji who is captured by the twelfth Angel, leading him to reflect on his loneliness and trauma from piloting the Eva. As the episodes progress, they culminate with the revealing of the “Human Instrumentality Project”. The project aims to “force the completion of human evolution” by breaking down the physical and psychological barriers that separate individual human beings. This would signify the “next stage of humanity, ending all conflict, loneliness and pain brought about by individual existence”[5]. In this process, known as Instrumentality, all of humanity will merge into one soul, creating transcendental abstract levels of existence where nobody existed singularly, but merely as part of one collective hive mind. Thus, Instrumentality implies the disintegration of the individual. The flaws in every living being would be erased and irrelevant, hence removing the fears and insecurities in people’s hearts that stem from imperfect understandings of one another. Therefore, a perfect existence is created without pain.

Shinji, who feels lonely and rejected by the people around him, stands at the epicentre of Instrumentality and is given a choice – to embrace Instrumentality, or to reject it and let humans become individuals once again. Although initiating Instrumentality at first, he chooses the latter in the end, and gives humanity the choice to revert to their bodily selves, recognising that a life with pain and mistrust is still worth living. Evangelion ends with Shinji and Asuka having washed up on a beach, the children of a world reborn.

Subverting The Apocalypse

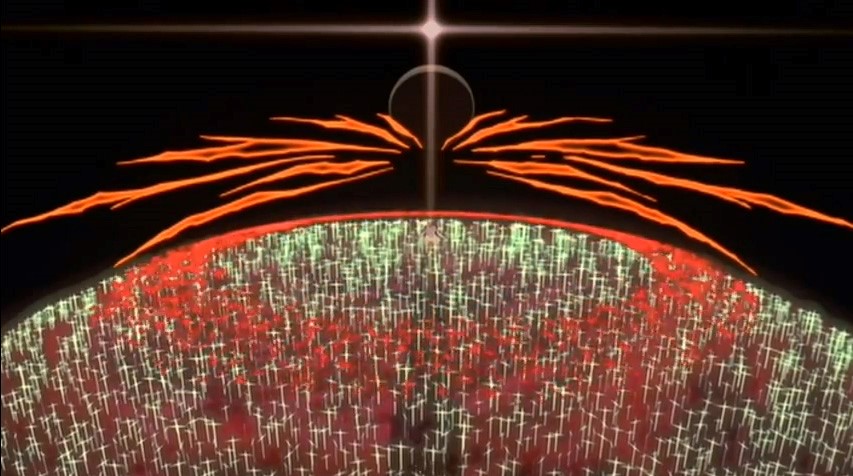

Evangelion contains many biblical and Judeo-Christian references to the apocalypse. The Japanese title translates to “Gospel of the New Century”. Moreover, the context of the series centres around powerful beings known as “Angels” coming down to Earth to destroy the world in service of creating a new one in God’s image. This parallels the flood myth found in chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis. Even the destruction of an Angel is denoted by a cross.

Hence, the aesthetics and context of Evangelion’s story reflect biblical understandings of the apocalypse. This ‘Judeo-Christian Apocalypse’ shares many similarities with the classical apocalypse, as both entail a foreign threat to society. Barkman recognises that the Angels and Christianity are seen as a “dangerous, alien religion” in Evangelion, and could be read as an allegory for foreign “impact” on Japan[6]. This is made even more ironic given the fact that angels are supposed to be benevolent messengers of God. However, an interesting thing to note about Evangelion is that most of the information about the Angels is largely inconsequential. Most of this information is found outside of the series itself. That is because the Angels are not meant to be the focal point of the show. Instead, Evangelion seeks to explore its core theme of loneliness by interrogating the inner psyche and neurosis of the Eva pilots. In fact, as Instrumentality becomes the new catastrophe, it departs significantly from the classical apocalypse. While “the Bible shows the judgement of the Old Earth to be a matter of justice and the creation of the New Earth to be a place where the just can find sanctuary again”, Evangelion “depicts the destruction and rebirth of the Earth in monistic terms”[7]. A clear distinction is thus made between the classical apocalypse and the new apocalypse. Instrumentality subverts the expectation of the Angel apocalypse; in that it introduces a new threat to humanity that contradicts the traditional apocalyptic threat. It is in this contradiction where we will find differing apocalyptic languages.

A Lonely Apocalypse

At its core, Evangelion follows the Eva pilots and centres around their experiences, wherein the show’s themes of escapism and loneliness are conveyed. Indeed, the general existential dread of loneliness and inability to find happiness become the principal unifier of all the main characters. Shinji lost his mother at a young age, and his father abandoned him to focus on his job, only reaching out to him when he proved useful in piloting the Eva. Due to this neglect and need for human connection, Shinji grows to rely on the admiration and validation of others to feel wanted. Similarly, Asuka was abandoned by her mother, relying only on her ability to suppress her loneliness through a sense of superiority while Rei was a human clone that was never taught how to make human connections. When Instrumentality begins, Shinji is the sole individual left to decide between embracing Instrumentality or rejecting it. This leads to a dream sequence that judges and examines his ego and identity. In it, Shinji is confronted by visions of Rei and Asuka who tell him that people can never be truly open with each other, as it entails being vulnerable to hurt and rejection, and people would rather keep things “vague” and “ambiguous”.

________________________________________________

“Because the truth causes everyone pain…because the truth is very very traumatic.”

-Rei Ayanami & Asuka Langley

________________________________________________

Asuka taunts Shinji, telling him that he only sought to help others because he wanted their validation, saying, “you never once loved yourself”. Desperate for human connection, Shinji begs Asuka, “Somebody help me! Don’t leave me alone…Anyone will do”. In so doing, Shinji will love anyone and as a result, he does not love himself. Asuka chastises him and rejects his plea. Shinji, unable to accept absolute loneliness, is consumed with nihilism and destructive impulses. He strangles Asuka, and initiates Instrumentality. He declares, “Nobody wants me, so they can all just die.”[8]. Therefore, Instrumentality grants the ultimate wish fulfilment for being alone and misunderstood, as all flaws and misunderstandings are wiped away, and all of humanity becomes one. No one can get hurt in Instrumentality. Since Shinji represents humanity, then humanity has chosen to escape reality. This is the true apocalypse in Evangelion.

________________________________________________

“I thought this was supposed to be a world without pain and without uncertainty.”

-Shinji Ikari

________________________________________________

Therefore, Evangelion’s apocalyptic language can be categorised into two major distinctions – religious and allegorical. Aesthetically, it draws upon Judeo-Christian elements to prop up its story. However, in terms of its message and themes, Evangelion is more akin to a metaphor for overcoming escapism as Shinji ultimately rejects Instrumentality and learns to grow up by accepting to continue living despite hardship. It is in this hybridisation where Evangelion subverts the classical apocalyptic genre and explores its themes of escapism and loneliness through the Hikikomori.

Anxiety and Hikikomori in Japan

Tanaka notes that 1995 was a watershed year for Japanese society, as in one year, Japan experienced two “apocalyptic events” – those events being the Kobe earthquake and the Tokyo subway sarin attack[9]. Tanaka states that these two events “deeply shook” Japan, which “was already suffering from the collapse of the bubble economy”[10]. These events in 1995 were thus seen as failures in the social and collective order of Japan: the asset bubble burst was a failure in Japan’s faith in its post-war economic boom; the Kobe earthquake was seen as a failure of state-wide response to disasters; and the sarin attack was seen as a cultural failure – a loss of hopeful imagination at the end of the fictional age[11]. The solution then was to retreat from society. Hence, apocalypticism from 1995 features characters “who lack serious interpersonal relationships” as it “becomes difficult for the youth to establish their identities as mature member(s) of society”[12]. Evangelion thus illustrates this failure to reconcile with society through its portrayal of the Hikikomori. The Hikikomori are self-isolated shut-ins who refuse to work or go to school for months or years, and prefer to indulge in escapist mediums such as anime and manga as they, like Shinji, could not accept reality and chose to run away. Plata notes that the financial crisis of the lost decade “changed the rules of the game and the traditional work system of the (Japanese) salaryman”, in which the model of lifetime employment no longer held[13]. Thus, many young adults secluded themselves in their homes due to a sense of precarity in society. The term “Hikikomori” is relatively new, and only surfaced in Japan in the 2000s. Heinze and Thomas note that when the term had just entered society, the Hikikomori were seen as “deviant and selfish youngsters, (even) parasites”[14]. As a response to this negative image, many anime and manga have tried to justify the Hikikomori as a “a sustainable and autonomous individual existence” that challenged “outdated patterns of work life, consumption, and gender roles”[15]. An example is the shōnen manga Welcome to the NHK (2002) which seeks to portray the Hikikomori as kind and self-aware individuals[16]. Evangelion in contrast rejects this self-aggrandizing notion altogether, and seeks to offer an escape from social withdrawal, as if warning of the “postmodern subcultures” that would come to dominate otaku culture in the 21st Century[17]. Hence, Evangelion would come to capture the zeitgeist of the 1990s, wherein the desire to retreat from society engenders the “weakening (of) interpersonal relationships and communalities” as seen in Shinji[18].

Conclusion

Indeed, Evangelion is not only a subversion of the classical apocalypse, but also subverts the anime genre by reflecting the very behaviour of its audience back at them. It thus stands as a critique of social withdrawal, offering an optimistic outlook on life and encouraging shut-ins to reject escapism in favour of forging genuine human connection. Thankfully for humanity, Shinji ultimately chose to reject Instrumentality, giving them a second chance at understanding each other, in spite of the pain.

________________________________________________

“I hate myself. But, but maybe I could love myself. Maybe my life could have a greater value. That’s right! I am no more or less than myself. I am me. I want to be myself! I want to continue existing in this world! My life is worth living here!”

-Shinji Ikari

________________________________________________

References

[1] Tanaka, Motoko, “Apocalypticism in Postwar Japanese Fiction.” (PhD Diss., University of British Columbia, 2011), 8.

[2] Susan Napier, “Panic Sites: The Japanese Imagination of Disaster from Godzilla to Akira.” The Journal of Japanese Studies 19, no. 2 (1993): 330, https://doi.org/10.2307/132643

[3] Napier, 329.

[4] Anno Hideaki, “Neon Genesis Evangelion” [tv programme], Netflix, https://www.netflix.com/sg/title/81033445

[5] Tanaka, 155.

[6] Adam Barkman, “Anime, Manga and Christianity: A Comprehensive Analysis.” Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 9, no. 27 (2010): 32, ISSN: 1583-0039

[7] Barkman, 32.

[8] The End of Evangelion. DVD. Directed by Hideaki Anno. 1997; Tokyo: Gainax, 1997

[9] Tanaka, 65-68.

[10] Tanaka, 10.

[11] Tanaka, 68-69.

[12] Tanaka, ii-iii

[13] Laura Plata, “The Crisis of the Self in Neon Genesis Evangelion.” Kinema Club Conference for Film and Moving Images from Japan XIII. Reischauer Institute, Harvard University, 2014: 3

[14] Tuinstra, Jeroen. “Social Problems through Contemporary Culture: The Portrayal of Hikikomori in Japanese Anime.” (Master’s Thesis., Leiden University, 2016), 14

[15] Heinze, Ulrich., & Thomas, Penelope. “Self and salvation: visions of hikikomori in Japanese manga.” Contemporary Japan 26, no. 1 (2014): 152, doi: 10.1515/cj-2014-0007

[16] Heinze & Thomas, 160-163.

[17] Heinze & Thomas, 153.

[18] Tanaka, 8.